Image above: Gina Little releasing an upper air balloon with a light southerly wind blowing across the launching ramp. The Sable Island Station is in the background. The building with the dome and the red observation platform houses MSC’s office and operations.

The Meteorological Service of Canada has moved its aerology program from Sable Island to Canadian Forces Base Shearwater (CFB Shearwater). The base is located on the eastern shore of Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia. The last upper air balloon was launched from the Sable Island Station during the evening of August 20th, 2019.

MSC has a long history on Sable Island. Climatological record-keeping on the island began in 1871 with the establishment of MSC, and since 1891 has been one of the longest continuous collections of weather data in the Maritimes.

The Sable Island Station is now mostly owned and operated by Parks Canada. However, prior to the establishment of the national park in 2013, the station was owned and operated by MSC. The met service began construction of the station at the present site in 1944. The first infrastructure was installed to support an aerology program.

The discipline of aerology—the study of Earth’s atmosphere—began in 1944 with the use of sensors (radiosondes) carried aloft by gas-filled balloons. The global network of aerological sites includes 31 in Canada, and some 800 sites worldwide, with international standards set by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland). Balloons and radiosondes are launched twice a day at the same time (11:15 and 23:15 GMT) at all aerological stations. The information is used in weather forecasting and research. Sable Island was involved in the program from the beginning.

Although the primary responsibilities and activities of MSC personnel on Sable Island were collection of surface weather observations and aerological data, MSC’s station became a base for national and international atmospheric and climatological research and monitoring, and also provided infrastructure for all other groups operating on the island. During the next six decades, various buildings, towers and sensors were added as the roles of MSC and the station expanded.

MSC’s office and operations building on Sable Island. In the distance (to the right) is the air chemistry building, and to the left is the “hydrogen shed” where the aerological balloons were prepared and launched. The small white globe is a balloon released just moments before the photo was taken.

MSC’s office and operations building on Sable Island. In the distance (to the right) is the air chemistry building, and to the left is the “hydrogen shed” where the aerological balloons were prepared and launched. The small white globe is a balloon released just moments before the photo was taken.

When Parks Canada took over the Sable Island Station in 2013, MSC retained four of its buildings to support ongoing programs: office/operations, air chemistry, hydrogen shed, and personnel accommodations (the triplex).

The hydrogen shed, located south of the MSC office, was where the balloon was filled with gas. The building has two sections, one for generation and storage of hydrogen gas, and the other (the high-ceilinged inflation room) for preparation and release of the balloon. Hydrogen gas was generated by electrolysis: passing an electric current through water. Although most stations in Canada use helium gas to fill upper air balloons, using hydrogen generated on-site was not only far less expensive (the cost being roughly no more than the cost of electricity and equipment maintenance), but also meant that the Sable program was not dependent on deliveries of gas cylinders from the mainland.

Minutes before 8:15 am on a breezy July morning, with a 16 knot southerly wind blowing across the launching ramp, MSC’s meterological technician Kathryn Binnema stood ready to exit the inflation room and release the balloon and radiosonde.

Minutes before 8:15 am on a breezy July morning, with a 16 knot southerly wind blowing across the launching ramp, MSC’s meterological technician Kathryn Binnema stood ready to exit the inflation room and release the balloon and radiosonde.

A radiosonde is a small package of sensors. The sonde was prepared in the operations building and then taken to the hydrogen shed where it was attached to the inflated balloon. The inflation room has a high ceiling to accommodate the gas-filled balloons, and it has two large overhead doors, one facing east and one facing west. The technician decided which door to use based on wind direction and turbulence.

Twice a day on Sable Island (8:15 am and 8:15 pm, local time; 7:15 am & pm in winter), a radiosonde was launched and carried aloft to altitudes in excess of 30 km. As it rose through the upper atmosphere—through the troposphere and into the stratosphere—the radiosonde measured temperature, humidity, pressure, and wind speed and direction. These data, and the sonde’s position, were transmitted to the MSC operations building at the station where it was partly analysed, reduced to a coded message, and sent to MSC’s regional headquarters in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. The ascent of the balloon and radiosonde was usually called “the flight” by station staff.

Met techs Vic Duguay and Yves Sivret doing high wind releases in the 1980s. The Kaysam balloon (left) was eventually replaced with the Totex balloon (right) which was more expensive but tougher (a type originally identified as a “Severe Weather” balloon). As the technology advanced, the large radiosondes held by Vic and Yves were replaced with smaller instruments, and then even smaller models.

Met techs Vic Duguay and Yves Sivret doing high wind releases in the 1980s. The Kaysam balloon (left) was eventually replaced with the Totex balloon (right) which was more expensive but tougher (a type originally identified as a “Severe Weather” balloon). As the technology advanced, the large radiosondes held by Vic and Yves were replaced with smaller instruments, and then even smaller models.

Various types of balloons had been used in the Sable program, but all were made of latex and had to be handled with care. Sable Island was one of the windiest of MSC’s aerological stations. The balloon release required practice. Even in a moderate breeze, it could be a challenge. The technician had to guide the balloon out through the large doorway, making sure the balloon and instrument were not damaged. Turbulence around the building could cause the balloon to stretch, flap and twist in all directions, but the technician had to hang on and get the balloon out of the turbulence zone so that when released it would rise quickly. If it didn’t, the sonde could hit the ground or get tangled in a fence or tower.

Met tech Allison Taylor doing a release during a late December snowfall. The wind was east-northeasterly at 15 knots and Allison used the west-facing door so that she would have the wind at her back. In her left hand is the much smaller radiosonde in use during the past decade.

Met tech Allison Taylor doing a release during a late December snowfall. The wind was east-northeasterly at 15 knots and Allison used the west-facing door so that she would have the wind at her back. In her left hand is the much smaller radiosonde in use during the past decade.

Gina Little releasing in a 19 knot northwesterly wind on a blustery October evening. The wind grabbed the balloon as soon as Gina exited the inflation room, and she hurried to get the balloon and sonde away from the building for a safe launch.

Gina Little releasing in a 19 knot northwesterly wind on a blustery October evening. The wind grabbed the balloon as soon as Gina exited the inflation room, and she hurried to get the balloon and sonde away from the building for a safe launch.

Although Sable Island is one of the windier sites in Canada, there are many days with relatively light winds.

Although Sable Island is one of the windier sites in Canada, there are many days with relatively light winds.

In addition to the continuous and long-term collection of meteorological and aerological data, MSC’s Sable Island Station had participated in numerous national and international atmospheric research programs. Sable Island’s location “downwind” of North America led to its use as a platform for studies of air quality and long-range transport of air pollutants. Scientists with groups and agencies such as the Air Quality Branch (MSC), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the University of Rhode Island, and Princeton University, had initiated and participated in programs on Sable Island.

There were two broad categories of atmospheric research carried out on Sable Island: study of meteorological dynamics, and study of pollution. The former deals with topics such as interaction of weather systems and generation of storms; the latter addresses issues such as global warming and air-borne contaminants.

Study of Tropospheric Ozone

The study of tropospheric ozone (O3) is an example of the atmospheric research and monitoring that could be conducted at Sable Island because of the logistical support, data, and expertise provided by MSC’s upper air station.

Tropospheric O3 is a critical atmospheric species influencing chemical processes. It is a principal component of photochemical smog, and in the lower troposphere has significant implications for air quality and human health, and directly damages vegetation (forests and crops) and reduces yields. Sable Island is particularly important because it represents a transitional location between the polluted continent and the clean marine environment. Tropospheric O3 data had been collected at Sable in various studies since the late 1980s. Initially a summer project, studies were continued when it was found that O3 levels over Sable Island were higher than expected.

With the ongoing aerology and meteorology programs at the station, specialized ozone sensors could be deployed as add-ons to the daily radiosonde flights, with relevant ground-based measurements. In August 2006, the station participated in an international study of tropospheric O3, the INTEX Ozone Network Study (IONS-06). Using the station’s aerology facilities, ozonesondes were launched once a day, with the evening radiosonde.

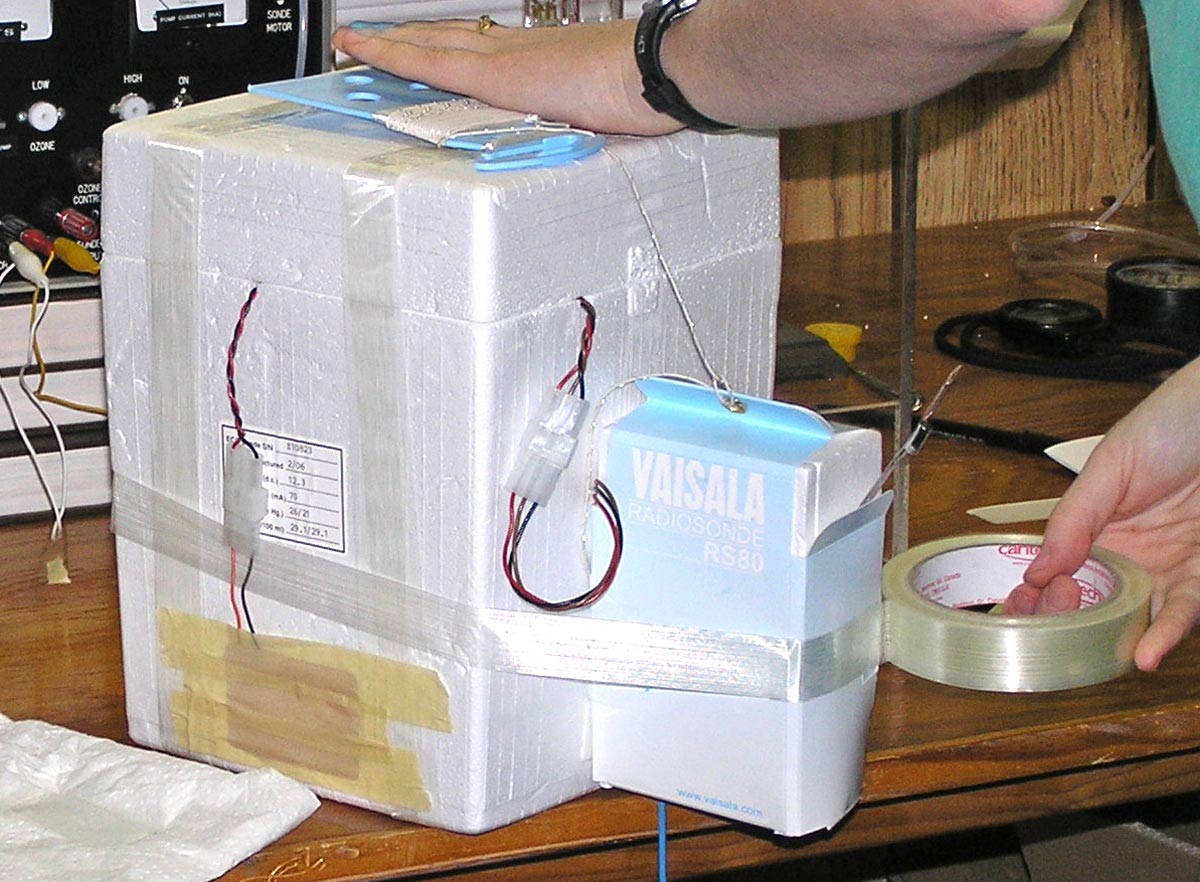

To collect ozone profiles (i.e., vertical distribution) an O3 sensor was coupled to an aerology radiosonde.

To collect ozone profiles (i.e., vertical distribution) an O3 sensor was coupled to an aerology radiosonde.

The ozone sensor was contained in a large polystyrene box (25 cm high). The smaller radiosonde was attached to the ozonesonde with double-sided tape, and a wrapping of fibre tape provided additional security. The ozone sensor was coupled to the modified radiosonde so that humidity, temperature, pressure, wind, and geopotential height could be measured simultaneously with ozone sampling, and all these data were transmitted by the radiosonde to the surface.

An ozonesonde coupled with a radiosonde, launched by Gina Little in a light wind, southwesterly at 6 knots. The balloon was inflated with an extra 500 grams of hydrogen (50% more than normally used for an aerological launch). The extra gas was needed to lift the combined weight of the ozonesonde and the radiosonde.

An ozonesonde coupled with a radiosonde, launched by Gina Little in a light wind, southwesterly at 6 knots. The balloon was inflated with an extra 500 grams of hydrogen (50% more than normally used for an aerological launch). The extra gas was needed to lift the combined weight of the ozonesonde and the radiosonde.

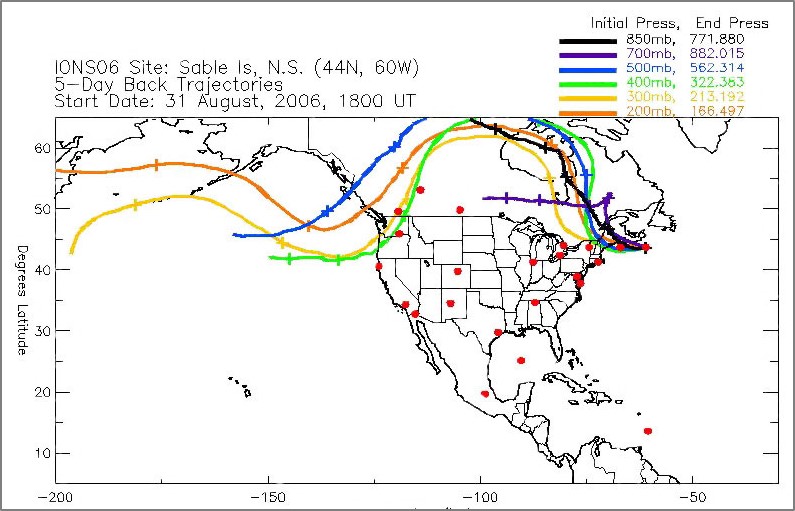

As data were collected from the network of O3 profiling sites, back trajectories were computed to show the path followed by air masses before they were sampled. This provided information on the sources of pollutants and an understanding of how they might have been modified along the way. These could represent polluted air from different sources (i.e., different locations on the continent). Analyses of various parameters, including winds, enabled researchers to identify the geographical origins of the polluted air (e.g., Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario).

In the images below, the pressure (mb) levels also represent approximate heights (e.g., 850 mb = 1500 m; 200 mb = 12,000 m). So the black line represents the air closest to the surface. The trajectories show that air at different altitudes can move in very different directions and speeds. Trajectories at lower elevations are shorter because lower air parcels do not move as fast as upper air parcels.

A five-day back trajectory for the last Sable Island sampling in the IONS 2006 study. Back trajectories were computed to show the path followed by air parcels before they were sampled at Sable. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

A five-day back trajectory for the last Sable Island sampling in the IONS 2006 study. Back trajectories were computed to show the path followed by air parcels before they were sampled at Sable. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

The forward trajectory for the same flight (i.e., August 31st), computed to show movement of air parcels during four days after they had been sampled at Sable Island. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

The forward trajectory for the same flight (i.e., August 31st), computed to show movement of air parcels during four days after they had been sampled at Sable Island. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

A decal for the 2006 program, with red dots indicating the participating sites in Canada, the USA and Mexico. The two Nova Scotian sites (Yarmouth and Sable Island) are dots in the centre of the image.

A decal for the 2006 program, with red dots indicating the participating sites in Canada, the USA and Mexico. The two Nova Scotian sites (Yarmouth and Sable Island) are dots in the centre of the image.

In summer 2008, the Sable Island Station participated in another international ozone research project (IONS-08). Among the objectives were study of sources and transport of pollutants affecting the arctic atmosphere, and study of ozone precursors and particulates generated by forest fires. During this period, forest fire plumes influenced the ozone profiles of six sampling days at Sable Island.

A back trajectory plot showing that sampling at Sable (on July 9th 2008) had picked up pollutants from forest fires in southwestern USA and southern Canada. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

A back trajectory plot showing that sampling at Sable (on July 9th 2008) had picked up pollutants from forest fires in southwestern USA and southern Canada. (Image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA).

The national and international significance of data collected at Sable Island during the tropospheric ozone studies demonstrates the scope and importance of the MSC’s role on the island. With the closure of the aerology program, the expertise and capacity that had been provided by MSC on Sable Island is no longer available to support similar levels of atmospheric research and monitoring, and scientific collaborations.

The Last Flight

With the aerology unit installed at CFB Shearwater, flights were conducted at both Shearwater and Sable for several days. Once it was confirmed that the Shearwater site was operating consistently and reliably, the upper air program on Sable Island was shut down.

August 20th 2019, 8:15 pm. The last upper air balloon from WSA Sable Island was launched by MSC’s David Hartlin.

August 20th 2019, 8:15 pm. The last upper air balloon from WSA Sable Island was launched by MSC’s David Hartlin.

At the time of release, conditions measured at the station were 20°C with a northwesterly wind at 7 knots—a gentle breeze for the launch. By the time the balloon burst, it had ascended for 1 hr 47 minutes, reached a height of 34.5 km (pressure 6.5 hPa), and was roughly 80 km east of Sable Island.

And so ended Sable Island’s aerological program, the last balloon gone quietly up into the dark on a foggy night.

August 21st 2019, 8:15 am. Without a hydrogen-filled balloon and activated radiosonde awaiting launch, the large overhead door of the inflation room remained closed. This was the first morning of a new era, a significantly changed human presence on Sable Island.

August 21st 2019, 8:15 am. Without a hydrogen-filled balloon and activated radiosonde awaiting launch, the large overhead door of the inflation room remained closed. This was the first morning of a new era, a significantly changed human presence on Sable Island.

August 21st 2019. For the first time in decades, without an evening upper air flight underway, there was no one in the MSC operations building and the lights were off.

August 21st 2019. For the first time in decades, without an evening upper air flight underway, there was no one in the MSC operations building and the lights were off.

The island has been a national park for six years. The Meteorological Service of Canada’s upper air station had been on Sable Island for 75 years. For three of those decades the station had served as one of Canada’s more important atmospheric research data acquisition sites.

Although the aerology program is gone, and upper air personnel are no longer stationed on the island, MSC continues to maintain several programs using automated instrumentation and sensors. These are a) Reference Climate Station (measurements of temperature, wind, precipitation, pressure, snow depth, and sky radiation); b) greenhouse gas monitoring (measurements of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide); and c) air shed monitoring (measurements of ozone, oxides of sulfur and nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and aerosol particles).

A comprehensive review of the history and roles of the Meteorological Service on Sable Island—operations and programs, aerology, meteorology and atmospheric research and monitoring, and cultural legacy—is in preparation.

Some persons who served as MSC met techs on Sable Island share memories and some thoughts about their experience:

Merlin MacAulay (1955-1956)

Gordon LeBlanc (1963-1964)

David Millar (1967-1969)

Brent Kempton (1978-1979)

Isabelle MacDonald (2013)

Allison Taylor (2015-2016)

Mike Maurice (2017)

Kimberley Forsythe (2013, 2017-2018)

And see Gina Little (2007-2019)

Other items related to MSC’s role on Sable Island:

Roll Clouds of Sable Island

Sable Island Roll Cloud of June 2003

Clean-up of an Old Fuel Cache

For some who remember Sable’s balloon launches, tracking flights …

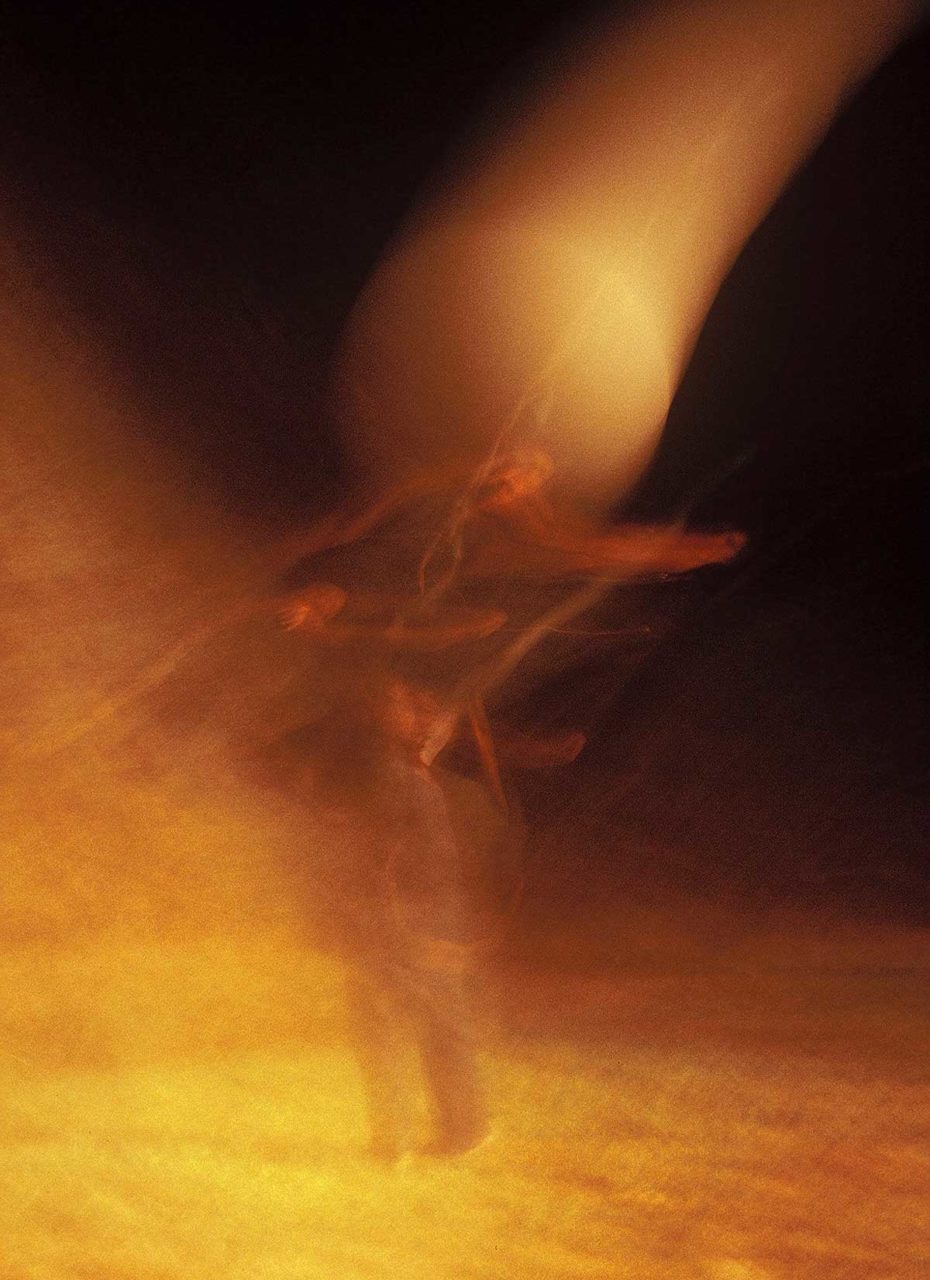

… perhaps at night a glow appears near the hydrogen shed, a brief shimmering as if a figure and a balloon are whirling in a high wind release, a glimpse of thousands of launches, gas-filled balloons, strings and sondes, and energy, collapsed into a momentary flicker of light, then gone.

… perhaps at night a glow appears near the hydrogen shed, a brief shimmering as if a figure and a balloon are whirling in a high wind release, a glimpse of thousands of launches, gas-filled balloons, strings and sondes, and energy, collapsed into a momentary flicker of light, then gone.

Zoe Lucas

Sable Island Institute, August 2019

11 Responses

15 minutes of reading has given me with a lifetime of station wisdom… and now the sadness that this unbroken streak of valuable data has come to an end

I am interested as to what happened to all the balloons and the items that are carried along. Are you able to get them back and reuse them?

Just when more information is needed, an irreplaceable unbroken stream of data is ended. Profoundly sad and disheartening.

This is a distressing report. At this time of frightening climate change, to cancel such a program is appalling.

Served as OIC Sable back in the mid 70’s. Great memories of the Island, the ponies and the seals. Sunday drives around the Island, and could never forget Zoe, the one constant on the Island

A met tech named Lynn Batstone served at Sable in the 1960’s or 1970’s.

I knew him in the 1990’s when he was carrying out surface weather observing at Red Lake, ON and then Island Lake, MB.

He had his share of good Sable stories,

Bruce Mullock

Toronto

In about 48 hours Sable Island will greet the full force of Hurricane Fiona. It will see wind speeds not seen since 1976. Back then, with alot of the equipment destroyed and continous generator power failures, we were down to what was left for us as mechanical recordings. Our barograph continued it’s clicking every 2 mb of pressure change. We sat and watched the odometer. The needle was bent from hitting the endstop which was at 108 MPH. Our best estimates came in at 120 MPH gusts. We couldn’t take proper temperature readings as the Stevenson screen was blown away. It was reported that this was not a CAT 3 hurricane as the low pressure system did not form in warm enough waters! What we all remembered the most from that night was the tremendous noise. It was like being in a metal garbage can and people beating on that can with a baseball bat. The next day, a Sunday, I was able to make contact with the radio station in Halifax to get word out of the damage and help required. Our offices on the mainland were closed on Sundays with no emergency number contact. After the news report the DJ was kind enough to play our request of “windy” by the Fifth Dimention.

Mark Varrin

Acting Officer-in-Charge, Sable island, 1976

spent a year on Sable in ’70/’71. Sable was a dream posting, swimming with the seals was an unforgettable experience.

Satellites will never replace on site data, especially atmospheric chemistry ( my field ’74 – ‘2002 ).

Canada needs to be extending sovereignty ( note re Arctic ) instead of abandoning locations like Sable

– Alan Gallant

Saw on tv the other night that there is a Parks Canada job posting on the island currently and it got me thinking of what happened to MSC on Sable, then I found this sight. What a shame the program is no longer going on there. I spent 3 months as a tech from just before Christmas 2006 (we had a nice turkey dinner…thanks again Zoe!) to March 2007. Lots of good memories from my short stint there, including launching a ballon in wicked winds…took two tries with Gerry’s help). I was supposed to go back in the summer but switched over to the Water Survey of Canada and never went back. I recently retired and will always remember my time on that magical island.

Too bad. Again the regional office has hauled in another function into the Halifax area. Starting with the aviation forecast operations in Moncton to the weather radar which should have been a downstream warning site along the south shore as the military had done, and now the upper air operations which would have been one of MSCs few contributions to ocean operations. It would have been better at Canso but that is not Halifax. Why not bring the UA operations in Yarmouth to Halifax as well.

Good comment Ken!

At this perilous time in our nation’s history we need visionaries, not accountants !