Image above: Transect C-C2 surveyed May 25th 2020—counting sparrows and looking for banded individuals.

Ipswich Sparrows, a subspecies of the widespread Savannah Sparrow, is one of Sable Island’s most interesting and iconic nesting birds. After the summer breeding season, the sparrows leave the island and migrate to their wintering grounds in the coastal regions of eastern USA. The Delmarva Peninsula (a 274 km-long peninsula occupied by parts of Delaware, Maryland and Virginia) is a particularly important wintering area for Ipswich Sparrows. Come spring, they return to their Sable Island breeding grounds.

The Ipswich Sparrow is listed under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in Canada as being a Special Concern. Their restricted summer and winter ranges and small population size (roughly 6000 individuals) make them especially vulnerable to impacts such as habitat loss, increased predation, and extreme weather events.

To better understand how such challenges might affect the survival of the Ipswich Sparrow, researchers are banding birds on Sable Island and on the Delmarva Peninsula with combinations of coloured plastic leg bands that identify individuals. As these banded sparrows are subsequently recorded in regular band resighting surveys in the summer and winter locations, the data provide insights regarding survival rates and potential threats during the Ipswich Sparrow’s breeding, migration, and overwintering life cycle stages.

With the Sable Island National Park closed because of COVID-19, Parks Canada has had a small team on the island to maintain basic station operations. Since the Ipswich Sparrow research team was unable to travel to Sable to conduct the spring 2020 survey, Parks Canada’s Greg Stroud and Brent Ford completed the survey during late May. This is the first of two resighting surveys per year. Another will be done in late summer/fall.

Sable Island in late March. This aerial photo, taken as the aircraft approached the landing strip on the beach, shows the freshwater pond Pinetree East, and floodwater on the south beach. The three black specks in the middle of the photo are Sable horses.

Sable Island in late March. This aerial photo, taken as the aircraft approached the landing strip on the beach, shows the freshwater pond Pinetree East, and floodwater on the south beach. The three black specks in the middle of the photo are Sable horses.

In March and April the landscape looks mostly grey and bleak, with a slight hint of green, but this is home and safe haven for Ipswich Sparrows who have just completed a flight over the ocean. Although small numbers (a few hundred) have been recorded overwintering on the island, most of the sparrow population flies south in autumn and returns to Sable Island in early spring.

Two Ipswich Sparrows in late April, one standing on the wooden boardwalk at the Sable Island Station, and the other in a patch of weathered crowberry. Photos Greg Stroud.

Two Ipswich Sparrows in late April, one standing on the wooden boardwalk at the Sable Island Station, and the other in a patch of weathered crowberry. Photos Greg Stroud.

The Bird Bands

This sparrow, standing on a concrete path at the Sable Island Station, was banded near the station in fall 2018. Having been born in summer 2018, it is now almost two years old, and in its third calendar year of life. This bird has been seen repeatedly in the same area, and is probably a resident of the vegetated terrain inside the station compound. Photo Greg Stroud.

This sparrow, standing on a concrete path at the Sable Island Station, was banded near the station in fall 2018. Having been born in summer 2018, it is now almost two years old, and in its third calendar year of life. This bird has been seen repeatedly in the same area, and is probably a resident of the vegetated terrain inside the station compound. Photo Greg Stroud.

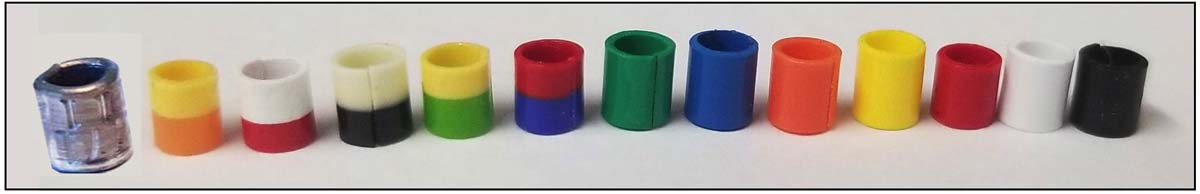

Coloured plastic bands can be used in hundreds of combinations to create a unique identification for individual birds. Photo Sydney Bliss.

Coloured plastic bands can be used in hundreds of combinations to create a unique identification for individual birds. Photo Sydney Bliss.

All the solid colours shown above (and also pink, which is not shown), and the white/red and white/black split colours, have been used on Sable Island. The Ipswich Sparrows have one plastic colour band over an aluminum band on one leg, and, three plastic colour bands on the other leg. In this project to date, 677 sparrows have been banded on the island (265 in 2017, 314 in 2018, and 98 in 2019).

The metal band shown at the left is made of aluminum. All birds banded in North America must have an aluminum band that is issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). These bands are stamped with a unique number. For example, the number on the metal band on the right leg of the sparrow above is # 2471-65258. Together with Canada’s Bird Banding Office (BBO), the USFWS regulates banding activities and keeps track of each one of the millions of birds banded annually.

The Resighting Survey

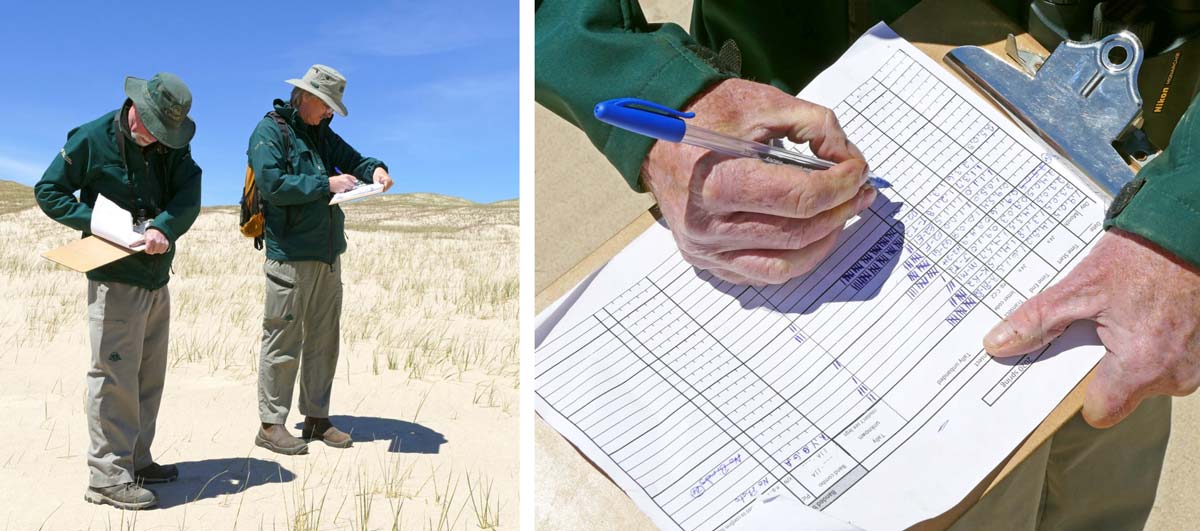

Parks Canada’s Brent Ford and Greg Stroud prepare to begin the resighting survey for transect C-C2. They are equipped with binoculars, a GPS unit with survey transect coordinates, and datasheets and clipboards.

Parks Canada’s Brent Ford and Greg Stroud prepare to begin the resighting survey for transect C-C2. They are equipped with binoculars, a GPS unit with survey transect coordinates, and datasheets and clipboards.

The surveys must be done during days with low wind (<14 knots, or <25 km/h), no rain, and good visibility. Wind and rain affect sparrow behaviour by causing them to shelter close to the ground, so the birds are less visible and the band colour combinations are difficult to read. Although the survey could be done anytime between mid-May to the end of the first week in June, favourable weather allowed Greg and Brent to begin the survey on May 19th and complete it on May 27th. During that period, a total of 2.5 days were spent on the survey program.

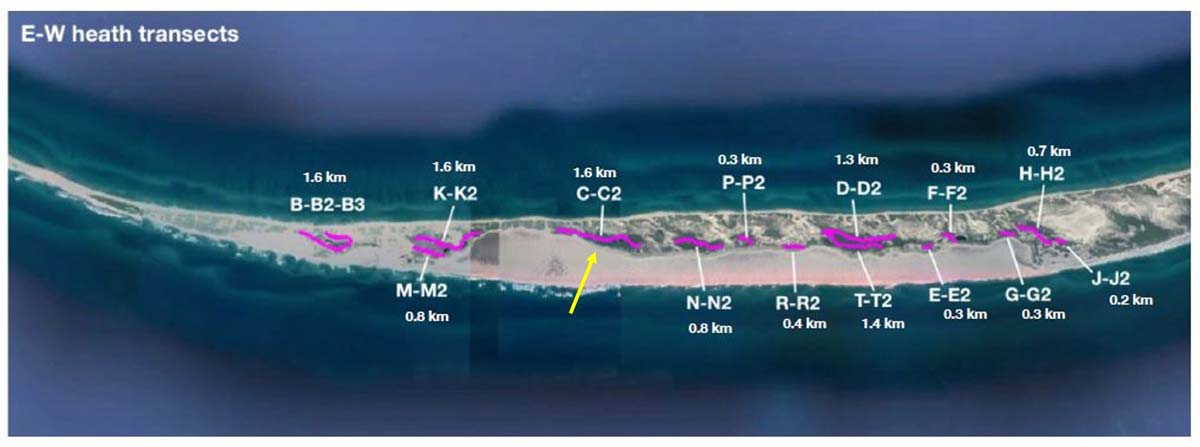

The western half of Sable Island, showing the 14 transects in terrain dominated by shrub-heath vegetation. Transect lengths ranged from 0.2 km to 1.6 km, totalling 11.6 km. The yellow arrow indicates transect C-C2, the 1.6 km-long track surveyed on May 25th (running between the Roseate Bricks area in the west, and almost to Gull Pond in the east). Image Sydney Bliss.

The western half of Sable Island, showing the 14 transects in terrain dominated by shrub-heath vegetation. Transect lengths ranged from 0.2 km to 1.6 km, totalling 11.6 km. The yellow arrow indicates transect C-C2, the 1.6 km-long track surveyed on May 25th (running between the Roseate Bricks area in the west, and almost to Gull Pond in the east). Image Sydney Bliss.

Greg checks the coordinates for the transect and will use the GPS unit to view the route and ensure that he and Brent are walking along the established transect line.

Greg checks the coordinates for the transect and will use the GPS unit to view the route and ensure that he and Brent are walking along the established transect line.

Just beginning the survey, and still in the western end of the survey track, Greg and Brent are tiny dots in the distance. They are walking 20 m apart, and each is recording any sparrows seen within 10 m to the right and 10 m to the left. So, Greg and Brent are each covering 20 m, which means that the transect is 40 m wide.

Just beginning the survey, and still in the western end of the survey track, Greg and Brent are tiny dots in the distance. They are walking 20 m apart, and each is recording any sparrows seen within 10 m to the right and 10 m to the left. So, Greg and Brent are each covering 20 m, which means that the transect is 40 m wide.

With its pale, sandy and brown plumage, the Ipswich Sparrow can be difficult to see amonsgt the weathered and sand-blasted vegetation of early spring—dry, yellowed grass and grey twigs. Photo Greg Stroud.

With its pale, sandy and brown plumage, the Ipswich Sparrow can be difficult to see amonsgt the weathered and sand-blasted vegetation of early spring—dry, yellowed grass and grey twigs. Photo Greg Stroud.

Transect lines were designed to go through the middle of patches of shrub-heath vegetation, optimum habitat for nesting Ipswich Sparrows. However, the shape and extent of these patches may have changed since the survey program was established in 2017. If the route provided no longer goes through the middle of a shrub-heath habitat area, the survey track is adjusted so that transect runs through the middle of the patch.

When an Ipswich Sparrow is seen, Greg or Brent try to get a good look at its legs to see if it is banded. If so, they stop the survey and together determine the band colour combination. They carefully examine the bands and discuss what they believe the combination to be. The band information is recorded on the datasheet of the observer who first saw the sparrow.

Greg and Brent walking towards the eastern end of the C-C2 transect (with a couple of horses grazing in the distance). By the time they had completed the 1.6 km transect, they had recorded a total of 85 Ipswich Sparrows, two of which were banded.

Greg and Brent walking towards the eastern end of the C-C2 transect (with a couple of horses grazing in the distance). By the time they had completed the 1.6 km transect, they had recorded a total of 85 Ipswich Sparrows, two of which were banded.

A brightly colourful Cape May Warbler. Seven non-sparrow species were sighted during the surveys: Wood Duck, Willet, Black-bellied Plover, and Blackpoll, Black-and-white, Palm, and Cape May warblers. All are far more conspicuous than the Ipswich Sparrow. Photo Greg Stroud.

A brightly colourful Cape May Warbler. Seven non-sparrow species were sighted during the surveys: Wood Duck, Willet, Black-bellied Plover, and Blackpoll, Black-and-white, Palm, and Cape May warblers. All are far more conspicuous than the Ipswich Sparrow. Photo Greg Stroud.

Brent Ford (Asset Maintenance Worker) and Greg Stroud (Operations Coordinator), Sable Island National Park Reserve.

Brent Ford (Asset Maintenance Worker) and Greg Stroud (Operations Coordinator), Sable Island National Park Reserve.

While conducting the survey, Greg and Brent had few opportunities to take photos of the Ipswiches. However, the six photos above show how inconspicuous these sparrows are in their sandy habitat in early spring before the yellow and grey colours of dead grass and twigs are replaced by the rich greens of summer.

The Numbers

The total recorded for the 14 transects was 416 birds, of which five were banded.

In addition to the records collected during the transect surveys, during April and May, Greg recorded 22 different banded birds near the station and in other areas, bringing the total to 27 banded sparrows resighted on Sable Island this spring. Sightings of any banded sparrows that are seen outside of the resighting surveys are valuable. These records can be used in calculations of survival rates and may provide some insights regarding behaviour.

The Demography Project Team

The Ipswich Sparrow demography project is a partnership between Acadia University, Dalhousie University, and the Center of Conservation Biology (Virginia, College of William & Mary). The lead researchers are Phil Taylor (Acadia), Andy Horn (Sable Island Institute and Dalhousie University), and Bryan Watts (CCB)—they initiated the project and will head up the data analysis and modelling. Sydney Bliss, a biologist with the project, manages the groundwork in Canada, including all fieldwork, data compilation, and communications. She works with citizen scientists to assist with resighting along the Atlantic Coast, and is the primary liaison with the CCB and also helps with field work on the Delmarva Peninsula wintering grounds. Sydney keeps track of all the colour band combinations used in both Canada and the USA. At the CCB, biologists Laura Duval and Chance Hines manage the program on the Ipswich Sparrow’s wintering grounds, including resighting surveys and banding. The group is currently in the early stages of data analysis and should have results soon. The project began in 2017 and the plan is to continue until at least 2022.

Note: The Delmarva Peninsula, so important in the life history of Sable’s Ipswich Sparrows, is within the boundaries of three states from which the name Delmarva is formed: Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia.

Thanks to Sydney Bliss for generously sharing information about the project and results.

Zoe Lucas

Sable Island Institute, June 2020

For more about Sable’s Ipswich Sparrows:

Ipswich Sparrow Demography Project

Just a Gray Bird (Andy Horn, 2017)

Birds with Bling, Banding Ipswich Sparrows (Andy Horn, 2018)

And about the Sable Island National Park Reserve:

Sable Island National Park Reserve

Parks Canada

Also see:

Sable Island, Just a Wink in the Sea (Greg Stroud, 2020)