Image above: Ipswich Sparrow perched on a driftwood branch on Sable Island. Photo Zoe Lucas

Everyone remembers their first. Their first Ipswich Sparrow, I mean.

My first was on a visit to Plum Island, a barrier beach along the north shore of Massachusetts. I only got to go there occasionally, by the grace of a brother who was old enough to drive. I lived for those trips, every one a chance to see birds I had no hope of seeing in our urban neighbourhood near Boston.

From spring to fall, Plum Island is famed for all sorts of birds that migrate through its marshes and scrubby woods. But in winter, our first stop was always the outer beach. There we’d scramble over the dunes and walk long lengths of the beach, scanning hard for just one bird: a pale species of sparrow that could be seen only on those coastal sands, and only in winter.

Often, foiled by jagged winter gusts, tiresome slumping sand, or simply the invisibility of the birds themselves (their plumage adaptively sandy against the sand), we’d return to the car without seeing even one. But the effort fed the mystery, heightening our excitement when we succeeded.

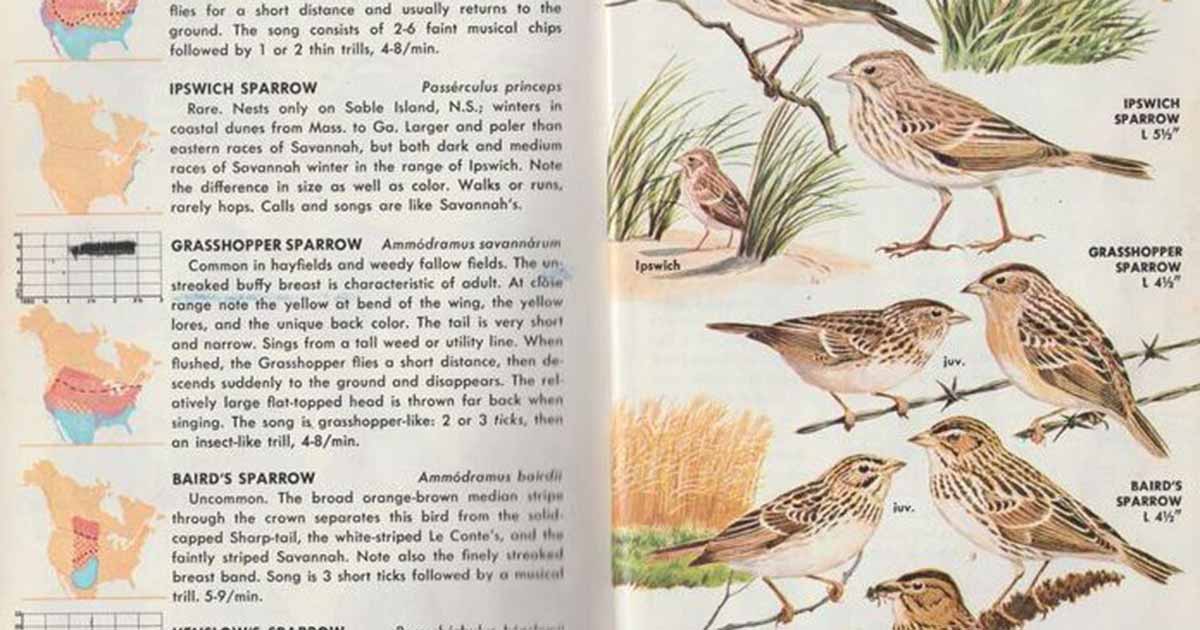

The bird, of course, was the Ipswich Sparrow, Sable Island’s endemic songbird, named for the place where a keen naturalist first discovered it in Ipswich, just a couple miles from where I first saw my first, but a century before.

Oddly, this bird breeds only on Sable Island, but winters on outer dunes stretching from Nova Scotia to Massachusetts, and beyond, southward to Florida. Why it insists on this yearly journey is a mystery. I like to think, as much based on the romance of the idea as on actual evidence, that its wintering habit is a return to its ancestral home, the preglacial coastal prairie that once stretched from Nova Scotia south to Florida — a coastal plain that disappeared with the shrinking icecaps, taking with it one of its last surviving endemic birds, the Heath Hen (which fires and predatory birds finished off on Martha’s Vineyard, in the 1930s).

Sable Island is often celebrated for its uniqueness, and rightly so, but for me this connection to its past especially resonates. Out of sight to most of us out in the Atlantic, the island remains, an ancient coast’s sand toehold on the edge of the continental shelf. And, stuck right to it all along, is a remnant endemic bird that, with its beady little brain, doggedly gambles every spring that it will find that sole sandspit in the great wide ocean.

How most North American naturalists first learn of Sable Island: from the pages of their bird guide. This is the one I used before I could drive—and before the American Ornithologists’ Union decided [alas!] that the Ipswich Sparrow is not a species, but just a race of Savannah Sparrow. (Robbins, C. S., B. Bruun, and H. S. Zim. 1966. A Guide to Field Identification, Birds of North America. New York, NY. Golden Press. 340 pp.)

Andy Horn

Sable Island Institute, September 2017