Image above: Wreck of the tern schooner George A. Wood. It was stranded and lost on Sable Island in December 1929. (Photo Forewell Family).

Introduction by Jennifer Forewell

Walter Blank was born in Eastern Passage and married Blanche Wells also of Eastern Passage. Walter was a fisherman, farmer, wireless operator, lighthouse keeper, and master of a lifesaving station in his life. Walter and Blanche had five children at the time they came to Sable Island in 1916: Hilda, Stella, Edith, Elsie, and Earl; Elsie was two years old at the time. They lived on the island for about 14 years.

Elsie later married Fred Forewell of Halifax and moved to British Columbia in 1946. She retained strong memories of her time on Sable Island and shared her memories with her family. In 1985 Elsie had requested and received permission to come back to the island, but didn’t make the trip. She tape-recorded her memories in 1988. She died in 2007. The following is an unedited transcript of Elsie’s account.

Life on Sable Island: A transcript of a 1988 recording by Elsie (Blank) Forewell

I’m sitting here tonight thinking—I’ve been doing a lot of thinking the past three and a half years—and somehow it takes me back in time.

When I was a kid of about four, my dad got a job on Sable Island at one of the lifesaving stations. It was Number 3 Station. It was in the centre of the Island. It was the most beautiful place on the Island. We had one man on the station with us to help with the hay-making and the cow milking and, of course, looking after and keeping all the life boats in repair in case of a shipwreck. There was wild cattle on the Island when we went there. We couldn’t go beyond the fences on account of the cattle. But then it didn’t take long and somehow they seemed to round them up in the corral and for beef cattle. And then from then on it was safe for us to go out and we could walk out beyond the fences.

We had just about everything there when you sit and think about it today. Dad used to plant the beautiful gardens. We had lots of fields for the horses, all fenced in, called them pastures—the lower and upper pasture. We had a place for the haymaking there in the upper field. Beautiful gardens. Dad used to do all the planting and we just had heaven there with the all the berries and everything on the Island. Mother was such a wonderful cook. She used to cook and all the lovely pies she made. My favourite was the strawberry pie.

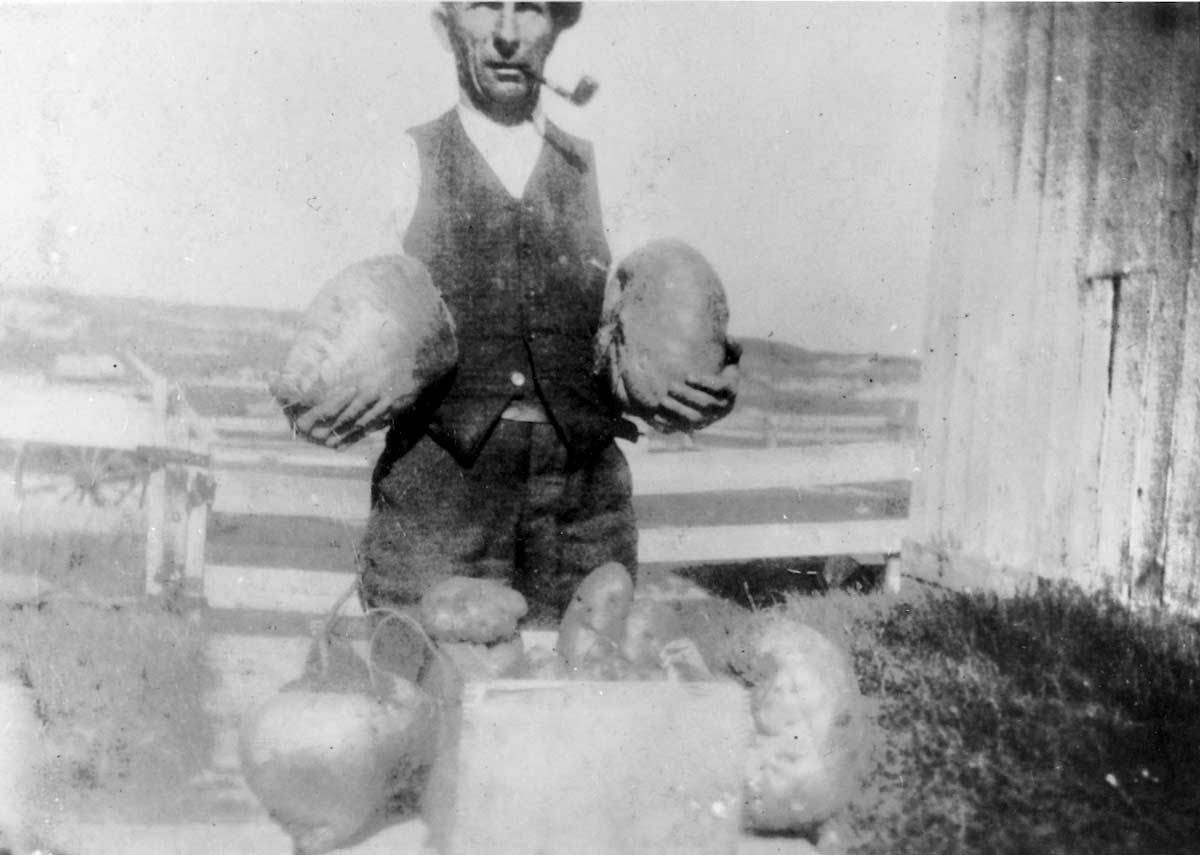

Walter Blank with a selection of huge vegetables grown on Sable Island.

Walter Blank with a selection of huge vegetables grown on Sable Island.

In Chapter 11 of the novel “The Nymph and the Lamp” (Raddall, 1950), the character Matthew Carney describes the island’s residents, and mentions a family at the No.3 Station: “Four miles further east you come to Number Three…another patrol station, chap with a big family, has a garden, grows the biggest potatoes and turnips you ever saw in your life, mixture of sand and pony manure—amazing!” (Note ZL; photo courtesy of Dalhousie University Archives and Special Collections, Thomas Head Raddall fonds.)

We had eight cows, ten horses, and lots of hens, and chickens and geese, and two dogs—Gipsy and Robin.

Dad was a lovely rider. He taught us all how to ride. He said, “There is more to riding than setting on a horse. You have to know what your horse is really thinking when you are out riding down in the valleys and a bird flies out of the grass. Keep your knees tight to your horse. And if your horse should throw you, you get right back on him. Let him know that you are not afraid of him.” I’ve never forgotten what Dad had taught us.

My sister and brother and I had to go every day to get the milk cows at 4 o’clock. Some days they’d be miles from home. We used to ride Dad’s horses till we got our own horses. I’d love to go down to the north, over to the north ridge and look down at the breakers breaking on the white shifting sands. Somehow they seemed to be saying something to me.

A Horse of My Own

Now a few years pass. I’m nine years old now and I have a western saddle of my own. When I first started to ride Dad taught me to ride with the saddle he made for me because I was too small for a western saddle to get the stirrups up to fit me. But now I have a western saddle of my own. And I’ve been in a couple of round ups getting the wild horses in the pound to ship off to the mainland. Each time we’ve been on a round up the next day my voice was gone. Mother would have to get the goose grease out and rub my neck to get my voice back.

I was out riding every day looking for a horse of my own. Then one cold October day I was out riding on old Jerry when I saw a colt standing by his dead mother. When he saw me he ran away but he came back. He was running back and forth so I lassoed him but I couldn’t hold him. Then he came back. I let him go and then I got on old Jerry and he came back again so I let him get to know Jerry and I started for home. He followed me. He still had the rope on his neck. That was the longest miles I’ve ever put in. When I got home to the barn Dad was there and he looked at me and said, “Bobby, where did you find him?” I said, “Dad, I found him standing by his dead mother and I want him for my very own.” It took us a long time to get him in the barn. At last he followed Jerry in the barn. We got him in the box stall. He was really not a little colt; he was a yearling. I was with him everyday after that.

Then one day Dad said, “Bobby, I think it’s time to halter break him.” And so we got the halter on him, put the rope to the halter and one on his front leg and then we got him out of the barn. There was a post in the centre of the corral. It was for halter breaking. [Dad said, “Hook the] rope to the post.” I did. He went down twice. Then he stood there looking at me. Dad said, “Bobby, take the rope off the post. Put it to the other side of his halter.” I did and then he said to me, “Now lead him around the corral.” I did. Then Prince was halter broken. Dad said, “Now in a few days, we will saddle break him. But first what are you going to call him? He has to have a name.” I said I am going to call him Prince.

Why I am saying so much about Prince…he is the one that came with me when we left the island. I said to Dad, “I don’t want to leave my Island. I am not going without Prince. When the boat gets here I will run away and no one will ever find me.”

A Baby Brother

Now let’s go back in time again. Time went by. I love my island more and more each day. I love to ride down in the valleys, smell the beautiful wild roses and the lily of the valley. We are still on Number 3 station. Mother had a baby. Dad brought him into the world. I remember we were out riding, looking for a horse for my brother. When we came home Dad came out of the bedroom and said to the three of us, “You have a baby brother.” I will never forget those words. But he wasn’t with us very long. He got sick and died just before he was two years old. Dad made his little coffin out of driftwood. He was buried over in Sleepy Valley.

There was another elderly lady with one head stone there, She used to live at Number 3 station long before we went there. And she said if she should die while she is on the Island there’s where she would want to be buried – over in Sleepy Valley. So instead of one headstone there’s two now. Small. He had a big fence around the graves made up of planks because if it was a small fence the wild horses used to come up there to scratch and they would knock it down.”

In the late 1990s, two headstones were briefly exposed as winds scoured sand away from a small graveyard that had been long buried. It was near the base of a bare, steep slope (shown here in the distance) roughly north of the Old No.3 station.

In the late 1990s, two headstones were briefly exposed as winds scoured sand away from a small graveyard that had been long buried. It was near the base of a bare, steep slope (shown here in the distance) roughly north of the Old No.3 station.

Several layers of organic material (soil and plant fragments) indicated that there had been periods of relatively stable terrain and vegetation here in the past, including a time when the site could have been described as “Sleepy Valley”. Remnants of a plank fence surrounded the two graves. Engraved on one of the two headstones was: “In Loving Memory of Clyde W. infant son of Walter & Blanche Blank. Died May 11.1923 Age 13 mos. 21 days”. The graves were buried again within a few years. (Note & Photos Zoe Lucas)

We missed him so much but as time went on we were still looking for shipwrecks. One night we were up on the north ridge – my two sisters and my brother, and I on horseback. A beautiful night. We were looking down towards Number 4 and we seen a boat coming, it was a ship really, coming in and we said, “Oh it’s going to hit the reefs. It’s going to hit the reefs!” It did come over one reef and over the other. So we got on our horses and we galloped home to tell dad. When we got home he said, “Yes, they put in a wireless SOS to the main station.” Dad put the winch on and was lowering the lifeboat down on the wagon. And he said, “Why don’t you harness the horses?” See Dad taught us how to harness the horses for the wagon. One horse went in the shaves and one on each side. So we had to know how to set the reins. Some were short and some were long and we knew how to do it well. He taught us a few years before so it came in handy.

Shipwrecks and Rescues

In the meantime the SS Connolly was dropping all her cargo overboard which contained big rolls of brown paper and little kegs of the horseshoes. They had to unload the boat to see if they could get it off. They never did get the Connolly afloat. Finally she sank deeper and deeper in the sand. Finally she broke all up into pieces and drifted ashore on the beach. [Note ZL: The tern schooner M.P.Connolly, out of Québec bound for Newfoundland, was stranded August 8, 1918, crew saved. See Armstrong, 2010.]

Then it was a job for each station to gather up all the paper and the horseshoes to take them to the main station. They had to be shipped off to Nova Scotia. It was amazing all that brown paper, big rolls. Just take off the first layer and it was so hard and well packed it was perfect. So our job was to get all we could off the beaches and take it to the main station when the boat came it would take them back to Halifax.

It wasn’t too long after that we had another shipwreck off of Number 2 station. It was the SS Platea. It was a Greek freighter. It came over the reefs, an SOS put out, and Dad and them had to go and rescue them. Dad got to know the Captain, the Chief Engineer, and the Wireless Operator. The only ones that really could speak any bit of English. They got very fond of my dad and got to know him well. He said to dad one day while the tugs were there from Halifax trying to get the Platea off. There were two tugs. And he said, “Mr Blanc” he called him, not Blank, “Mr Blanc, why don’t you come to Greece with us. Bring your family and if you don’t like it within a year, we’ll bring you back to Canada.”

They carried all their livestock on the ship with them. They had one sheep. They gave us Maria. They had a calf, lots of chickens, our rabbits. And so they gave us two rabbits and the sheep we had at Number 3 station. Willie and Sadie. Well we put them out underneath the barn and after that that’s all we had was rabbits by the hundreds—all over the place. We had old Maria; she had a little lamb. In the summer Dad used to shear her, cut all the wool off of her. Then Mother would wash it all and we’d have to sit and pick it all apart. She used to make comforters for us for our bed. They were beautiful.

They did get the SS Platea off Sable Island. [Note ZL: The Greek steamer Platea, out of Genoa and bound for Québec, was stranded November 7, 1919, crew saved. The ship was floated in 1920. See Armstrong, 2010.] And after that the Chief Engineer and I think it was a Wireless Operator they sent letters to my two older sisters and one year each one of them got a diamond ring.

Before I go any further, my older sister was going with a young man from the main station what was called the men’s house. That was where all the young single men were. My sister and Jack left the Island to get married. And came back on the next boat and they took over Number 2 Station. He brought me back a pair of riding boots. They were two sizes too big for me but I wore them anyway. They were the last things I took off when I went to bed at night.

I was glad when Dad called me Bobby after the Bobolink bird. That’s the bird that nested out on the flats. If you got near her nest she spread her wings and pretended she was hurt so you would follow her and you wouldn’t find her nest. Then when she got so far away she’d fly back to the nest. I liked to be called after a bird. I didn’t like to be a girl. I had long, blonde hair. It was almost white. It wasn’t beautiful or anything. It was stringy but I loved to gallop in the breeze and my hair blowing free.

We Had Our Chores to Do

You see it wasn’t all play on the Island; we had our chores to do. If it would get foggy the hired man would do the south side and go up the beach and put the ticket in the box for the other one in the west end to pick it up. Dad had the north side. Many a morning we, my sister and I or my brother and I, would go up the north side patrolling the beach. A lot of mornings I used to go alone. It was a few miles up. We would go up the beach and come back down in the valley down through the Island. You see we had a trail, a wagon trail from one station to the other right down all through the Island. It was a beautiful drive when you ride on horse going down through the valley through the wagon trail.

Every month or two we had to have our chisels all sharp to cut the hooves of the horse. Trim them all up so they wouldn’t split. We didn’t wear horseshoes on Sable Island in the sand so with that and the harness and waxing the saddles, keeping the bridles and everything in ship shape we were very busy. And then in the evenings we would have to learn. We thought we did. Dad would have from 7-8 in the wintertime.

But you know something, everybody was studying but not me; I was a dreamer. In other words I was possessed. I was always dreaming of what I was going to do next. Where I was going. What herd of horses I was going to go and bring back closer to my station. Especially if I knew there was a mare going to have her new colt. I’d be up early in the morning and I’d ride for miles to round up the herd of wild horses to bring them closer to Number 3 station just in case the baby colt would be born and I’d be the first one to see him. So therefore I was busy every day looking and searching and living with the wild horses.

Then one day I was out riding on Prince. Now he was three years old. He was quite a lovely little stallion. One day he forgot that I was on his back. He saw a few mares in the distance and he squealed and he hollered and he reared and he jumped and he went on. I was holding on to him. All of a sudden my girth broke, the saddle flew off, and hit me between the eyes. The blood was flying all over the place. I think I was knocked out but I’m not really sure.

Anyway after I got up I ran to where Prince was and he circled around and came back ‘cause a stallion came back and chased him. Then I got hold of him and I went home. I was full of blood. My mother said, “Now this is it!” And my Dad took me aside and he said, “Bobby, there’s something I have to tell you. We have to operate on Prince so he won’t be a stallion anymore or your mother said you won’t be able to ride him.” Dad said, “It’ll take 2-3 weeks and he’ll be as good as new. And you’ll have a lovely little riding horse.” And after three weeks he was all better and I could ride him again.

But in the meantime I used to ride old Jerry or General or Frenchie. Any horse I wanted to ride I could have. As Dad always said, “Pick your horse, Bobby.” I did. Now years gone by old Jerry was getting old. He was the one I first learned to ride on. He was about 16 hands high. He was a big, old, bony horse. I used to ride him standing up in my bare feet, with my toes stuck in there, standing up riding old Jerry anywhere. I could take him anywhere. He didn’t shy with birds or anything. I was always really safe on old Jerry.

Haymaking Time

As I said before, it was not all play with us. We had a lot of chores to do. Especially at haymaking time. Dad used to go way up to the south side of the Island. And him and the handy man would cut all the hay down with their scythes it was called. Then in the evening we had to go up and help them to haystack it. Put it all into stacks for the night because there was dew came on the grass then. In the morning bright and early when the sun came out we had to go out and spread that out again and that went on for a couple days. Haymaking time. Then they got the big wagon when the hay was ready to be brought down to the barn, put the big side racks on, go up to the south side and pile all the hay on the wagon and bring it down and put it up into the loft in the barn. He did that so many times during the summer.

Then up in the upper field he had to go cut the oats and do the same thing with that. And bring that down to the barn when it was ready. So you see we were very busy kids.

Then we’d have to get the buckboard, two horses and the three of us would go up along the beach and gather seaweed. We had to gather seaweed that came ashore, dry it out that was for the smoke house for when Dad smoked pig in the fall and when he killed the pig. And on top of that we had to gather kelp. That’s the word we used for it. That’s the stuff they said had iron into it. We would bring that home and Mother would wash it and then we’d have to eat some of it. It was terrible stuff to eat.

Then on Sunday we had Sunday school class every Sunday in the great, big, old den from after lunch, 12 o’clock lunch, until 1. I was always sitting by the door waiting with my foot. Dad would be preaching to us when all of a sudden he’d say, “Bobby, pull in your foot. We’re not ready yet. The horses’ll be there when you go out. They’ll still be down there somewhere. You’ll find them.”

Making Mats and Picking Strawberries

And another thing we had to help with was when Dad killed the seals and made the mats for Mother. He had to put them in the frame and hang them outside and we’d have to get our chisels and scrape the fat all out of the skins and cure them while they were all in a frames. Dad had them all twined into the frames up against the barn with the sun shining on them. And we’d have to scrape them every day to get all the fat out of the hide until they were cured. They were there so many days. And we’d have to do that every day to help scrape and scrape and get all the fat out of the hides. When they were all ready and cured, he’d take them out of the frames and we’d have to break them with your hand, make them soft, get them just like kid before it was all finished.

Every saddle had a pad on it. Dad used to put the pad, the hide, cow hide on top of saddle pad and he’d sew it all in. So each one had a pad underneath there. Mine was usually a seal skin. The rest had the cow hides. We had the white seal skin.

Then one day Dad’s old cow, Bess, she was getting so old. She had a calf but she died while having her calf. Then Dad had taken the baby calf away from the mother but it was dead. It was called a non-born skin. He saved that for me and he cured that. So I had a non-born calf skin. It was not like the other skin. It was so soft. It was really like kid and Dad cut the same shape of my saddle and put little hooks on it—one on the horn, two on the back of the saddle. That was on top of my saddle. That’s where I sat on that. It was the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen.

Then we had to go, at strawberry picking time, pick all the strawberries for Mother to put down for preserves for the winter. We had little galvanized buckets, Dad had made a rig, I don’t know if it was made of steel or iron or something but it hung out from the saddle and hooked on a thing at the horn. So when you’re riding on horseback it didn’t hit the saddle. So we’d have to go out and fill our buckets and bring them home for Mother so she could put them down and make jam out of it for the winter.

We did the same for the blueberries. We’d go gather blueberries in the same way and bring them home for Mother to do. We could have strawberry pie in the winter or we could have blueberry pie in the winter. They were beautiful. Then in the fall there was cranberry raking time. Those were all shipped to the mainland. Each station had to get so many barrels. We had those big sugar barrels that sugar used to come in on the Island for our station. We had to fill so many up and take them to the main station and when the boat came in the fall it would take them to Halifax.

The Ship Brings Supplies

Now when the boat came with the supplies they had a big wagon shed, a big warehouse just up off from the beach just before you get to the main station. Dad was the head of that when the boat came in. He was the boss of putting all the stuff where it was supposed to go like the barrels and the sugar and the flour and all that. Each station got its supply. We’d have two trips up there to bring our supplies down. A barrel of sugar, a barrel of flour and all the other things. A barrel of the big cartwirls soda biscuits, gravy, barrel of those dried apricots, prunes, raisins, all the stuff for the baking and everything. Even to the yeast cakes. We got the whole supply to do for the three months. Everything, even a big tin of tea.

Everything came and then when they got all the groceries home and all the stuff, the next trip would be for bringing so many bales of hay, we would get so many bags of bran, so many bags of oats. Then we’d get so many bags of coal and stuff like that for to do for the winter.

My oldest sister, her girl friends were the daughters of the governor of the island so she used to spend a lot of time up there with them. Then my other sister, a little younger than her, her girl friend was at the East Light so she spent a lot of time down there. They were much older than we were so they didn’t go out riding as much as we did but they did and sometimes a whole bunch of us would go together way up the south side. A whole bunch of us and Mother too. And we used to go for an evening ride. It was really fun.

My two older sisters they helped mother a lot around—helping her with the cooking and the washing and everything. It was a big, big house to keep clean and trimming of the lamps. They all had to be kept clean and neat in the morning. They were busy too helping Mother while we were out helping our Dad.

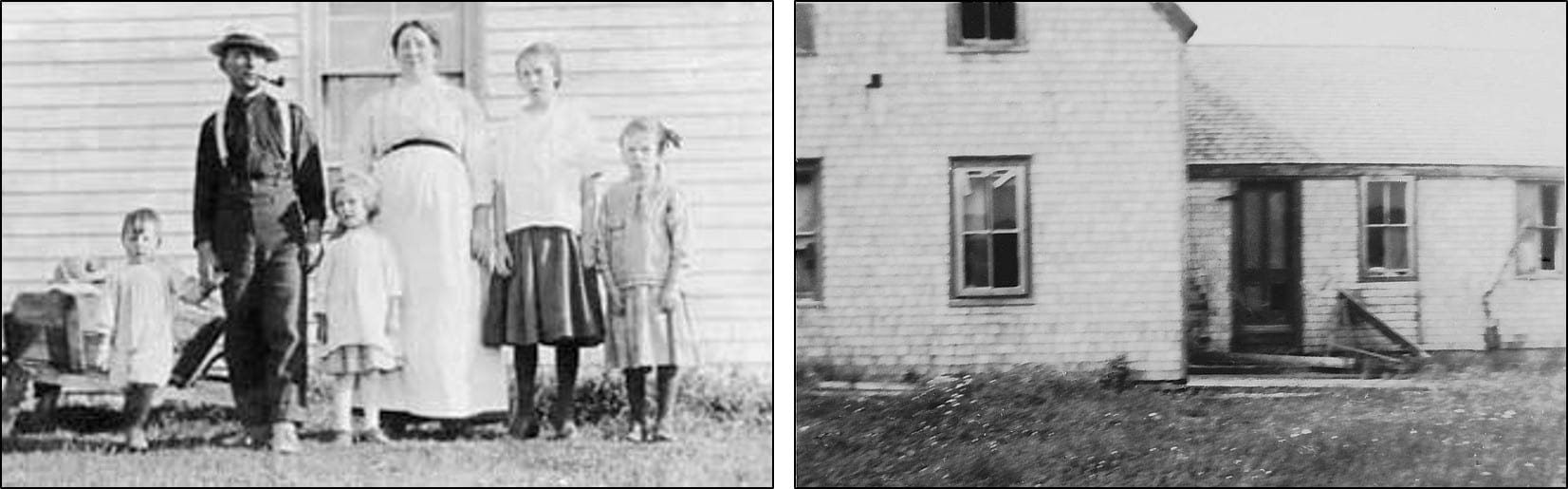

Walter Blank and his family on Sable Island, left to right, Earl, Walter, Elsie, Blanche, Stella and Edith (Hilda not shown) (photo courtesy of Dalhousie University Archives); and the Blank family home at the Number 3 Station (photo Forewell Family).

Walter Blank and his family on Sable Island, left to right, Earl, Walter, Elsie, Blanche, Stella and Edith (Hilda not shown) (photo courtesy of Dalhousie University Archives); and the Blank family home at the Number 3 Station (photo Forewell Family).

A Dory Full of Fish

Oh yes, we had two dories. They had drifted ashore. I guess they belonged to the fishermen. And through the years we had one and Dad and Mother had one. They used to go out fishing or fish in the summertime—a nice, fine, day. They used to go out and bring some cod fish home and they used to keep their dory up on the beach by the boathouse. One day it was fine and they were going out to do some fishing in the ocean and Dad said to us, “After you get the cows sorted bring the buckboard over so we can bring the fish home.” So we said, “Okay.”

They went out fishing; it was a lovely day but that day Dad didn’t take his compass. The fog shut in. Us three were on the buckboard waiting on the beach. A black fog came in. It was getting dark. Dad said he was lost out there but then he kept rowing around and they had a boat full of fish. Rowing around and he was listening and he could hear the gulls in the distance and he figured that was the direction to the island. So finally we were waiting on the beach and coming over the breakers there was the old dory with Mom and Dad into it and the boat full of fish. Us kids standing down there on the beach with the buckboard waiting for them and it was almost dark and we were really scared that we wouldn’t see them anymore.

So we had fresh fish and then Mother used to do a lot of drying the fish. Dried cod. That’s what I used to like—when she made fish patties out of the cod fish ‘cause it was really lovely. She dried the cod fish and we always had something different. Dad used to go out in the flats in the lake and get what we called the flat fish. I think they call them soles now. But the way Mother used to do them up they were lovely.

We kept our dory in the pond. Dad gave us one so we kept it in the ponds after we painted it all up. Then we got some boards and we made a little cabin in the dory. And we used to go from one pond to the other. But the largest, beautiful pond down there it had a divider of a little hill so we had what we called some rollers. We got some wood off the beach; it was called driftwood. And they were round poles so when we couldn’t get the dory to the other pond we had our rollers. We’d put the dory on the rollers and roll it on the other pond. Then we used to go down through the bullrushes.

A Duck Among the Chickens

There was a black nest, a black duck’s nest there and I watched her lay all the eggs. And every time she went out for lunch she’d cover the eggs with her down. And when she wasn’t looking I’d count the eggs. So finally she had about seven or eight eggs. And I waited for a few days and I went back and there was still the same amount so I thought she’s not having any more eggs. So I waited another few more days and I brought one home. And of course Dad had a lot of setting hens. He had a setting room for them with barrels they used to go in and had their little chicks.

So I asked Dad if I could put the black duck egg underneath the old hen. And he said, “You know Bobby, she’ll have to sit for another week.” And I said, “I don’t think so Dad. I’ve been watching that nest and I think she’d only have to set a couple more days ‘cause the black duck’s been setting there for nearly a week now on the same amount of eggs.” “Well” he said, “Bobby, maybe you’re right.” He took the egg and put it beneath the old hen. She just had one in there…just been a few days she was setting on hers. So we put the black duck’s egg underneath the old hen. And you know what? She only had to set about three days. After all the little chicks came out I had a little black duck.

You know, he was just like a little chicken. He was out in the hen yard. See we had a beautiful place for the hens and chickens and everything. All fenced off from the house. It had a pond and everything right in the chicken yard. And they could go over and nest in the grass or anything. That was the only problem that we had—the hens going and laying eggs and nesting out in the grass but they had a beautiful place there. Blackie grew up with the chickens. And when he got big he followed us all around the place, he’d be quack quacking in the evenings. He’d follow us all around the place and then when he got big he’d go out in the pond and do a lot of swimming, come back and go up by the old mother hen. He was getting too big to get underneath so he’d stay outside and sit by the old mother hen. He did that for the longest time. He was a big duck when he left and wouldn’t bother with the old mother hen anymore.

He used to go out on the pond every evening or way down through the ponds and you’d hear Blackie coming up quacking you know. We had our dory on the pond…in one of the ponds there so one night Blackie coming up quack quacking and I said, “Here comes Blackie” and all of a sudden he went down out of sight and he never came back. There was eels in the pond and Dad always said there must have been an eel that got Blackie. Well I’ve done a lot of crying over Blackie ‘cause I could hear his voice long after he was gone. I felt so sad for Blackie. Those eels in the pond Dad said must have got Blackie. So we never did see Blackie any more after that.

Every fall the wild geese used to always come over and land on the island, resting when they were going south. And every fall Dad would get one to two of the wild geese. Him and all old Gipsy—that was a water spaniel that we had—would go down and they’d be in the ponds and when Dad would shoot, Gipsy would go out and bring them ashore for Dad.

My Brother’s Little Horse

Oh yes, I forgot to say how my brother really got his little horse. Well the September before I got Prince…I found Prince in October. Well it was September, the month before, when we had the last round up at Number 3 station. That’s the year they rounded up all the horses in the corral. They took the stallions and the mares and they left all the yearlings run loose which I thought was very sad. They were running all over the place after their mothers and fathers were shipped to Halifax. There was one particular little chestnut mare. She got in with our work horses. She used to follow them home and around in the pasture. One day the fence was down and she came in. And every morning when we weren’t using the horses they all got their oats and bran. They used to always come down to the gates where the corral was looking for their breakfast oats and their bran.

So this little mare used to follow them and she got used to us. She’d come down and we’d give her some so after a while she’d come over to the fence and we used to give her carrots and sometimes those big soda biscuits. She liked them. We started patting her. She got to know us well. She was just a little pet. She wasn’t a bit scared of us or anything. So one day Dad said, “You know that would be a lovely little horse for your brother.” First thing we had the rope on her neck. She didn’t mind that. Dad says “Now,” one day “let’s try the halter on her.” We put the halter on her. She was just like one of our other horses. She was so tame that we could do anything with her.

So with me just having Prince then I was just training him. And we used to put them out together. She even walked in the barn one day. So my brother called her Queenie. So it was Queenie and Prince. They were always together after that. So then we put the saddle on her. Of course I had to be the first one to get onto her. She never even bucked. So that was my brother’s little horse.

Walter Blank and his family on Sable Island in 1917. In the back, daughters Stella and Hilda, seated in the middle, Blanche and Walter, and in front, daughters Edith and Elsie, and son Earl. (Photo Forewell Family)

Walter Blank and his family on Sable Island in 1917. In the back, daughters Stella and Hilda, seated in the middle, Blanche and Walter, and in front, daughters Edith and Elsie, and son Earl. (Photo Forewell Family)

Originally prepared for the Friends of the Green Horse Society;

all other rights reserved by the Forewell Family © 2012-2021

!!!<><><>!!!<><><>!!!

Additional Reading:

Raddall, Thomas H. 1950. The Nymph and the Lamp. McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. (2006 paperback edition, Nimbus Publishing Limited, Halifax, Nova Scotia)

Armstrong, Bruce. 1981. Sable Island. Doubleday Canada Limited. (2010 paperback edition, Formac Publishing Company Limited, Halifax, Nova Scotia)

11 Responses

That was quite a heartwarming story! I began to feel a sort of kinship with little Elsie as I too wanted a horse of my own when I was a child growing up on the farm. I never did get the chance though. But I think being able to visit Sable Island and have the chance to wander among the horses (especially all the mares and their frisky little foals) have somehow made up for not getting that horse of my own. Being able to visit Sable Island is one very wonderful memory that will forever bring me joy! And you know what? My dad’s two big work horses on the farm were called Queenie and Prince. I just couldn’t get over reading those names in Elsie’s story! She sounded a lot like my mother. Thanks for posting her words. I’ve enjoyed reading this!

So enjoyed this !

Growing up in a fishing village in N.S. may those memories so real?

a very interesting read for sure..

I loved reading this story, I have been wondering in this Blank family is the same family that eventually moved to Eastern Passage and settled on the Main Road where the Seniors Home is now. My Grandfather and Grandmother (Jim and Daisy Gill Horne), were also light house keepers and their six children were born on Sable Island. My Dad (the only boy) often said his best friends while he lived on the Island were the wild horses. My only regret is that I never found out more about their live on the Island.

WHAT A GREAT STORY ABOUT MY MOTHERS FAMILY GROWING UP ON SABLE ISLAND MOM TOLD ME A LOT OF GREAT STORIES ABOUT THE ISLAND MY MOM WAS STELLA BLANK AND AUNT HILDA AUNT ELSIE AUNT EDITH AND THEIR BROTHER EARL THANK YOU FOR THE HISTORY OF MY MOMS FAMILY NORMA STEPHENS DARTMOUTH NS CANADA

THANK YOU FOR THE LOVELY STORY ABOUT THE BLANK FAMILY MY MOTHERS FAMILY HISTORY WISH SHE WAS STILL ALIVE SO SHE COULD READ HER HISTORY NORMA STEPHENS DART NS

Such a wonderful story of my grandmother’s life on Sable Island. What an amazing opportunity to live in such a special place. I would love to visit and see the wild horses someday.

Lovely and interesting …I too was wondering if the Walter Blank was the same Blank family or relatives who lived in Eastern Passage NS…my Dads side were related to the Blanks…Thanks for posting..

Thank you to “Bobby”, to the person who transcribed the story of her remarkable childhood, and to the family who shared it!

Thank you for posting this story. Stella Blank was my grandmother (Lloyd Wilson’s mother). I see Aunt Norma (Dad’s sister) posted a note earlier. It sounds like life on Sable Island was idyllic for a child at that time. I appreciate (great) Aunt Elsie sharing her memories.

I loved Aunt Elsie,Dido’s story. Dido was my Moms Sisters-in-law and came to visit us in Nova Scotia when her family had grown. They were residents of British Columbia after leaving Nova Scotia. I came out to BC from Nova Scotia and stayed with Dido prior to finding a in BC.. I loved her stories of Sable Island, she rode horses in Burnaby for many years. An incredible woman.