For the past couple of years, the Sable Island Institute has been headquartered in a picturesque building with an intriguing history, the Gatekeeper’s Lodge at the entrance to Point Pleasant Park in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Built in 1896 as a dwelling for the park-keeper, it has a story-book appeal with its steep roof, stepped gables and finials. Despite its fanciful look, it is not the only building of this design; it was modelled after one specific gatehouse in England, known as Wycombe Lodge.

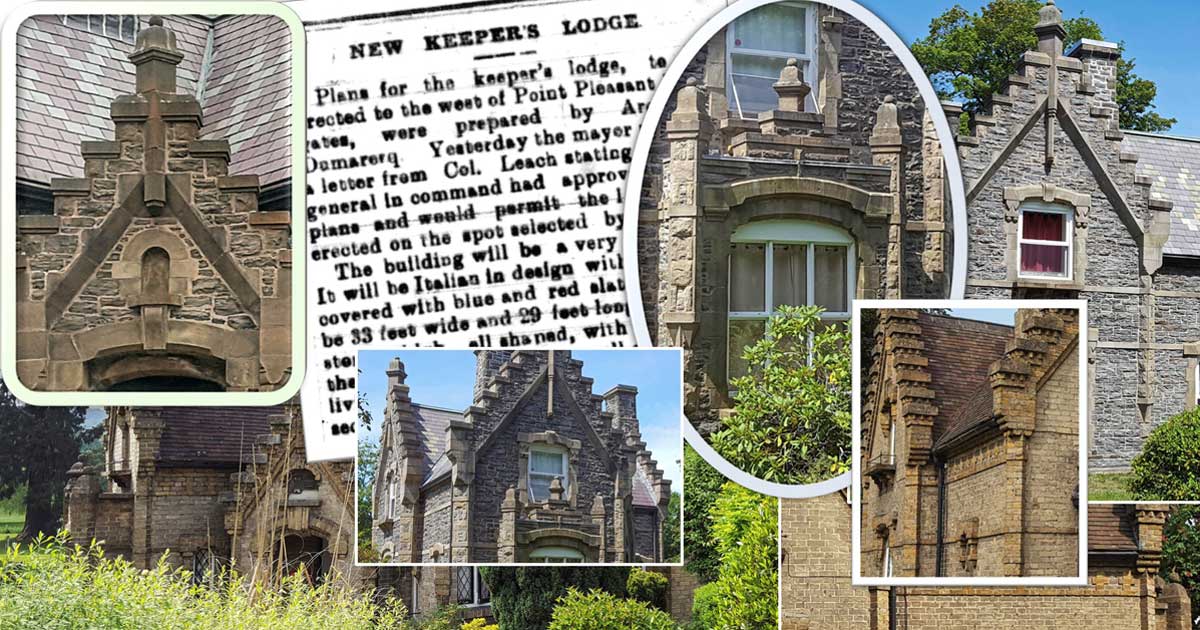

Front views of Wycombe Lodge, Buckinghamshire, England (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park, Halifax, Canada (right).

While in England in 2018, I visited Wycombe Lodge to take a closer look. It piqued my curiosity. How did this English gatehouse come to be the model for one in Nova Scotia? Who built these gatehouses, and was there a connection between them? What accounts for the design of these gatehouses? To try and answer these questions, I needed to delve into the architectural preferences of the time and the histories of the buildings and the people involved with them.

The Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Canada

We’ll begin with the Gatekeeper’s Lodge (also known as the Keeper’s Lodge, the Superintendent’s Lodge and Point Pleasant Park Lodge). In 1866, the Crown signed a 99-year lease with the ‘Directors of a Park at Point Pleasant’ (later known as the Point Pleasant Park Commission) for the 75-hectare promontory at the southern tip of the peninsula of Halifax for the sum of one shilling a year. This lease was later extended to 999 years, and the park was officially opened in 1873. About twenty years later, the directors decided that the park-keeper (the superintendent of the park) needed a dwelling, and in 1896, the prolific Maritime architect, James Charles Dumaresq was selected to build it.

J.C. Dumaresq had a very successful 36-year career and was responsible for over 250 buildings [1]; his career and the details of his buildings have been well documented by Monique Marie Carnell in The Life and Works of Maritime Architect J.C. Dumaresq (1840-1906) [2]. Dumaresq’s success was attributed to his versatility and willingness to work on all types of projects, without specializing in any one particular area of design. His “ability to effectively incorporate elements of the popular stylistic idioms of the day” [2] included styles such as Second Empire, Queen Anne Revival, Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival.

On June 16, 1896, Dumaresq placed a tender in the Halifax Herald [3]:

TO BUILDERS

Tenders for building Keeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park, will be received till Tuesday, 16th inst., at this office, where plans and specifications may be seen. Building to be stone.

Lowest or any tender not necessarily accepted.

J.C. DUMARESQ

Architect

197 Barrington St.

Samuel Manners Brookfield (1847-1924), considered “the most important building contractor in Nova Scotia” throughout his career [4], was awarded the contract. The stone mentioned in the tender was slate from a quarry within Point Pleasant Park.

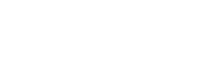

Construction of the lodge aroused interest in the people of Halifax and articles appeared in local newspapers. The Halifax Herald, April 23, 1896 featured an article describing the gatehouse [5]:

NEW KEEPER’S LODGE

Plans for the keeper’s lodge, to be erected to the west of Point Pleasant Park gates, were prepared by Architect Dumaresq. Yesterday the mayor received a letter from Col. Leach stating the general in command had approved of the plans and would permit the Lodge to be erected on the spot selected by the city. The building will be very pretty. It will be Italian in design with pitch roof covered with blue and red slates. It will be 33 feet wide and 29 feet long, and two storeys high, ell shaped, with a porch in the angle. The first floor will contain the living room, kitchen and washrooms. The second floor will be three bedrooms.

The gates mentioned in the article were donated to the city in 1886 by Sir William Young (1799-1887). Young, who was once premier of Nova Scotia and a chief justice, was also the first chairman of the Point Pleasant Park Commission and maintained a life-long interest in the park. The fine iron-wrought gates (made in Dartmouth) were attached to large granite pillars and were positioned at the end of what was later named Young Avenue, at the entrance to the park [7]. Ten years later, the keeper’s lodge would be built just beyond these gates, within the park.

The Halifax Herald article also stated that the lodge would be “Italian in design”. This probably referred to the Italianate style, which was popular in Halifax from 1850-1870, especially among commercial buildings [21]. Good examples are those on Granville Street, which were rebuilt after the fire of September 9, 1859 that destroyed 60 buildings. The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, built in 1868 as the customs house and post office, is another example of this style and was modelled on an Italian Renaissance palazzo. However, the newspaper was mistaken; the keeper’s lodge did not have Italianate style features, some of which include flat or low sloping roofs and round-headed windows.

The Morning Chronicle on November 21, 1896 reported further progress on the new lodge [6]. With the heading The Building Boom: Citizens Who Have Been Erecting New Homes-Buildings That are Credit to the City, the article stated that the “architect J.C. Dumaresq seems to get a good share of business in the city” and that he had prepared plans for six buildings, including Keeper’s Lodge. In fact, 1896 was Dumaresq’s most successful year, during which he worked on at least 18 projects [2].

By 1897, the lodge was ready for occupation. Its first tenant, the superintendent for the park, Samuel Venner lived there until his death in 1906 [7].

Although it is tempting to analyze the architectural style of the Gatekeeper’s Lodge in the context of popular idioms of the time or Dumaresq’s preferred styles, we need to remember that this gatehouse was modelled after another building. To put things into perspective, we need to cross to England and look at Wycombe Lodge.

Corner views: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

Corner views: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

Wycombe Lodge, England

Wycombe Lodge is located on the estate of Hughenden Manor in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire (about 47 km, or 29 miles, northwest of central London) and was built in 1870-1871 at the entrance to the second carriageway to the manor. To understand why Wycombe Lodge looks as it does, one first needs to look at Hughenden Manor and its prestigious owner, Benjamin Disraeli.

Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) was a British statesman, novelist and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in 1868 and 1874-1880, and had a close relationship with Queen Victoria, who appointed him the 1st Earl of Beaconsfield in 1876. Their friendship was such that she grieved his death in 1881 and had a large white marble memorial plaque erected in the church at Hughenden with the inscription [8]:

To the dear and honoured memory of Benjamin Earl of Beaconsfield.

This memorial is placed by his grateful sovereign and friend Victoria R.I.

“Kings loveth him that speaketh right” Proverbs xvi, 13

February 27, 1882

Disraeli inherited Hughenden Manor in 1848 on the death of his father, Isaac D’Israeli, who had purchased it in 1847 [9]. Benjamin Disraeli’s ownership of Hughenden Manor played a critical role in his becoming Prime Minister. At that time, it was essential that the leader of the Conservative Party (previously the Tory Party) represented a county and to do so, one had to be a landowner in that county [10]. Although Disraeli owned several houses, he and his wife were greatly attached to Hughenden. Disraeli’s wife, Mary Anne, worked extensively on the design of the gardens while Disraeli turned his attention to its architecture. The manor was of white stucco and unassuming in design in 1848 [11], but this changed dramatically when Disraeli, enthralled with the romance of Gothic Revival architecture, decided to have Hughenden Manor remodelled.

A little reminder about architectural styles: Gothic Revival (also known as Neo-Gothic or Victorian Gothic) was a style that became extremely popular during Queen Victoria’s reign, and harkened back to the romantic and picturesque features of medieval Gothic architecture, such as pointed arches, lancet windows, steep-sloping roofs, tracery and front-facing gables. However, many other types of revivalism (a revisiting of architectural styles of the past) had become popular in the nineteenth century, and some architects incorporated features from several styles into a single building. This is called architectural eclecticism and it appears to have played a role at Hughenden.

The architect that Disraeli hired to remodel Hughenden in 1862 was Edward Buckton Lamb (1806-1869). Lamb had the reputation of being a stylistic eccentric and an “architectural rogue elephant” for combining “medievalism and modernity, traditional forms and new materials” to create new architectural styles [12]. At Hughenden, he worked in a highly dramatized hybrid baronial form of Gothic architecture, incorporating such features as juxtaposing red brickwork, stepped battlements and pinnacles. The result pleased Disraeli enormously.

Disraeli then decided to have a gatehouse built at the entrance to a second carriageway to the manor. Named Wycombe Lodge, it was built in 1870-71 by George and Arthur Vernon of High Wycombe [13]. George Vernon was the land agent managing Hughenden Manor and his son, Arthur, had just finished his training as an architect in 1870 under Edward Buckton Lamb [14]. Although Wycombe Lodge was built in the same style as Hughenden Manor, the designation “Neo-Tudor” has been applied to this gatehouse (for unspecified reasons) in some reports [13]:

Wycombe Lodge

C19. Yellow brick, tiles. Neo-Tudor style with stepped gables. 1 storey and attics, lattice casements. Segmental arched gabled porch. Stone panel with shield on east side, stone panel with crest and coronet over porch arch. Listed largely for historical interest as an approach to Disraeli’s Manor House at Hughenden in Wycombe Rd.

Views facing the road: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

Views facing the road: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

Similarities and Differences Between the Two Gatehouses

Side-by-side photos of Wycombe Lodge (built in 1870-71) and the Gatekeeper’s Lodge (built in 1896) provide the opportunity to appreciate their similarities and differences.

The lodges are obviously the same basic design and display a variety of Gothic Revival features, including steep-sided roofs, finials (the ornaments on the apexes of roofs or pinnacles), hood moulds (the external, slightly rounded mouldings above windows that divert rain away from the window itself) and crow-stepped gables (step-like ornamentation along the ends of roofs). However, there are interesting differences in the finishing touches; these are, in part, due to their different building materials (yellow brick in Wycombe Lodge and slate in the Gatekeeper’s Lodge) but are also due to stylistic choices. A few of the differences include:

- The style and number of steps in the crow-stepped gables at each lodge

- The hood moulds above the windows at each lodge

- The roof tiles – patterned only at the Gatekeeper’s Lodge

- The frieze (brickwork pattern below the eaves) – only at Wycombe Lodge

- The styles of the windows (note their absence on one wall in the Gatekeeper’s Lodge)

- The pediments (above the doors).

Pediments: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right). The carving in the pediment at Wycombe Lodge depicts a castle and a crown. A castle occurs on the Disraeli coat of arms.

Pediments: Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right). The carving in the pediment at Wycombe Lodge depicts a castle and a crown. A castle occurs on the Disraeli coat of arms.

Side view (facing park): Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

Side view (facing park): Wycombe Lodge (left), and Gatekeeper’s Lodge, Point Pleasant Park (right).

The extensions on both lodges were added at later dates and are not similar. The extension on Wycombe Lodge is short, and the design is not in keeping with the original building. The extension on the Gatekeeper’s Lodge was added in 1950 [7]. A source of the same stone that was used in the construction of the gatehouse in 1896 was available for building the extension, and hence the extension almost looks as if it was part of the original building. The addition of ‘battlements’ to the top of the extension also helped maintain its character.

How did the Gatekeeper’s Lodge come to be modelled after Wycombe Lodge?

We have now looked at when each lodge was built, who built them, why they were built and what they look like. The next question is: How did someone in Canada come to know about Wycombe Lodge so that it became a model for a gatehouse at Point Pleasant Park?

1) Did one of the Point Pleasant Park Commissioners already have Wycombe Lodge in mind when they decided to build a keeper’s lodge in the park?

In 1894, a Commission report stated that “a neat brick cottage at the gateway of Young Avenue would form a suitable and convenient lodge” [7]. This indicates there was no specific building in mind at that time. I found no source that indicated the Commission acquired knowledge of Wycombe Lodge between 1894 and 1896, so it seems more likely that it was the architect, J.C. Dumaresq who somehow discovered it.

2) Could someone visiting Benjamin Disraeli at Hughenden Manor have remembered Wycombe Lodge and passed along this information?

As a statesman, Prime Minister, novelist and friend of Queen Victoria, Disraeli had many guests at Hughenden. But he died in 1881. The Gatekeeper’s Lodge was built in 1896. This seems too long a time to carry a good impression of a gatehouse passed by during a visit.

3) Could someone in the Vernon family (the architects for Wycombe Lodge) have recommended this gatehouse design?

The Vernon family rose to considerable prominence and became well-connected. Arthur Vernon designed many buildings in High Wycombe and, among his other achievements, became mayor of this town [14]. Arthur’s cousin, Walter Liberty Vernon (1846-1914) was born in High Wycombe and became a distinguished architect in Australia; his buildings are listed in national and state heritage registers [15]. Arthur Lazenby Liberty (a more-distant family member), founded Liberty’s of London in 1874. Despite their large fields of influence, I did not discover a link between the Vernon family and J.C. Dumaresq.

One tantalizing possibility is a connection between the Vernon family of High Wycombe and Ernest Daniel Vernon (1872-1941) of Truro, Nova Scotia. Ernest Vernon was born in England in 1872 and immigrated to Canada with his mother and two brothers in 1888 [16]. Ernest’s father (Charles Frederick Vernon) died in England sometime between 1876 and 1881, but I could find no ancestral or familial details about him. His name does not appear in the family history of the Vernon family of High Wycombe. But, in an odd twist of coincidence, Ernest trained as an architect in Halifax in 1893-1894 and continued architectural work for 40 years in a variety of styles including Queen Anne and Gothic Revival [17]. His dates put Ernest Vernon nearby when the Gatekeeper’s Lodge was constructed in 1896, but there is no evidence he had any involvement in it or communicated any knowledge of Wycombe Lodge to J.C. Dumaresq. It is unlikely (given his age when he emigrated to Canada) that he had any knowledge of Wycombe Lodge.

4) How might J.C. Dumaresq have come to know about Wycombe Lodge?

There was no school of architecture in Canada until McGill University opened one in 1896. Formal training for architects was limited to articled pupillage in the Maritime provinces during most of the second half of the nineteenth century, and there was no association of architects in Nova Scotia until 1932 [18]. Thus, Dumaresq could not have heard about Wycombe Lodge through an organized body of architects. There is a possibility he heard about it from individual architects working in the Maritimes, but I could find no evidence to support this. His busy building schedule throughout the 1880s and 1890s would suggest Dumaresq did not see Wycombe Lodge himself.

However, there were two periodicals, The Builder (1843-1966) published in England and the monthly Canadian Architect & Builder (1888-1908) that contained wide-ranging information about architectural designs, plans and materials [19]. The possibility exists Dumaresq spotted something about Wycombe Lodge in one of these.

Regretfully, I found no answer to the question. The means by which the Gatekeeper’s Lodge came to be modelled after Wycombe Lodge remains a mystery.

What is not a mystery is that the fanciful design of Wycombe Lodge, however it came to their attention, appealed to Dumaresq and to the Point Pleasant Park Commission. Gothic Revival and other revivalist styles of architecture were highly fashionable in the nineteenth century, and Dumaresq had been designing and constructing many buildings in these styles throughout the Maritimes. The story-book charm of an English gatehouse inspired the construction of a nearly identical one in Canada, and both gatehouses continue to charm today.

Epilogue:

Hughenden Manor became a property of the National Trust in 1947 and is open to the public. In the cellars, its wartime secrets are revealed: Hughenden was used as a secret intelligence base where maps were created for bombing missions, including Hitler’s bunker. Because of this Hughenden was once at the top of Hitler’s hit list [20].

Wycombe Lodge is the property of the Wycombe District Council and is let as a private residence.

The Gatekeeper’s Lodge is managed by the Halifax Regional Municipality and is currently occupied by the Sable Island Institute. For information about current activities at the Lodge, visit The Sable Island Institute at Point Pleasant Park.

Janet Godsell

Prepared for the Sable Island Institute, April 2019

Note: Janet Godsell spent time on Sable Island in the 1980s while conducting research on grey and harbour seals, and while working as an exhibit planner for the Nova Scotia Museum on the 1989 exhibit “Sable Island: A Story of Survival” that explored the human and natural history of Sable Island.

References

1. Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950. Dumaresq, James Charles Philip (1840-1906). http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/1649

2. The Life and Works of Maritime Architect J.C. Dumaresq (1840-1906) by Monique Marie Carnell, 1993. http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/ftp04/mq23851.pdf

3. Halifax Herald, June 16, 1896, p.5, c.6. Nova Scotia Archives.

4. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Brookfield, Samuel Manners. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brookfield_samuel_manners_15E.html

5. Halifax Herald, April 23, 1896, p.3, c.4. Nova Scotia Archives.

6. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), November 21,1896, p.6, c.2. Nova Scotia Archives.

7. Point Pleasant Park, An Illustrated History by Janet Kitz & Gary Castle, 1999. Pleasant Point Publishing.

8. Geograph. Disraeli Memorial. https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4031718

9. Parishes: Hughenden, in A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 3, ed. William Page (London, 1925), pp. 57-62. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol3/

10. Darwin Porter, Danforth Prince Frommer’s England 2006 pg. 243 Frommer’s, Book&Map edition (2005) Online https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hughenden_Manor

11. Hughenden Manor, https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/hughenden-manor

12. Victorian Rogue Architecture. “The Demotic Gothic of the 1860s” by George P. Landow. http://www.victorianweb.org/art/architecture/rogue.html

13. Hughenden Park Management Plan, 2016-2026. https://www.wycombe.gov.uk/uploads/public/documents/Parks-and-woodland/Hughenden-Park-management-plan.pdf

14. Archiseek. Vernon, Arthur (1846 – ) http://archiseek.com/2009/arthur-vernon-1846/

15. June’s Story. Walter Liberty Vernon. http://junesutherland.com.au/vernon.html

16. Ponting Family History Vol.IV – Chapter 9. Mary Vernon nee Veness. https://www.ponting-family-history.org/vol-iv-chapter-9/

17. Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950. Vernon, Ernest Daniel. http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/93

18. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Canadian Architecture 1867-1914. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-architecture-1867-1914

19. The Canadian Architect and Builder. http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06627

20. BBC News. Secret base’s WWII role revealed. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/beds/bucks/herts/4481611.stm

21. Italianate Halifax 1850-1870. https://halifaxbloggers.ca/builthalifax/2017/10/italianate-halifax-1850-1870/

2 Responses

That was very interesting.

It knew Mr.Firipps( spelling ??) that lived there.

Then , Mr . Nickerson lived there with his family. They had previously lived

in Fort Olgivie in Point Pleasant Park.

My good friend Jim lived in both places.

I visited him in both places.

We used to call it ” The Hassle Castle”.

Those were the days my friend. 1950/ 60’s.

These gates were known as The Golden Gates.

Many great hockey players got their start on the Quarry Pond just behind the Lodge.

This Park is unique. Imagine if the people that established it could see it now.

It was my back yard, play place, picnic area,

Music was played in Band Stands, dog walking, people walking, running and many other activities etc.

Thank you for having the foresight you people of long ago. Point Pleasant Park is greatly appreciated by all people that now use it.