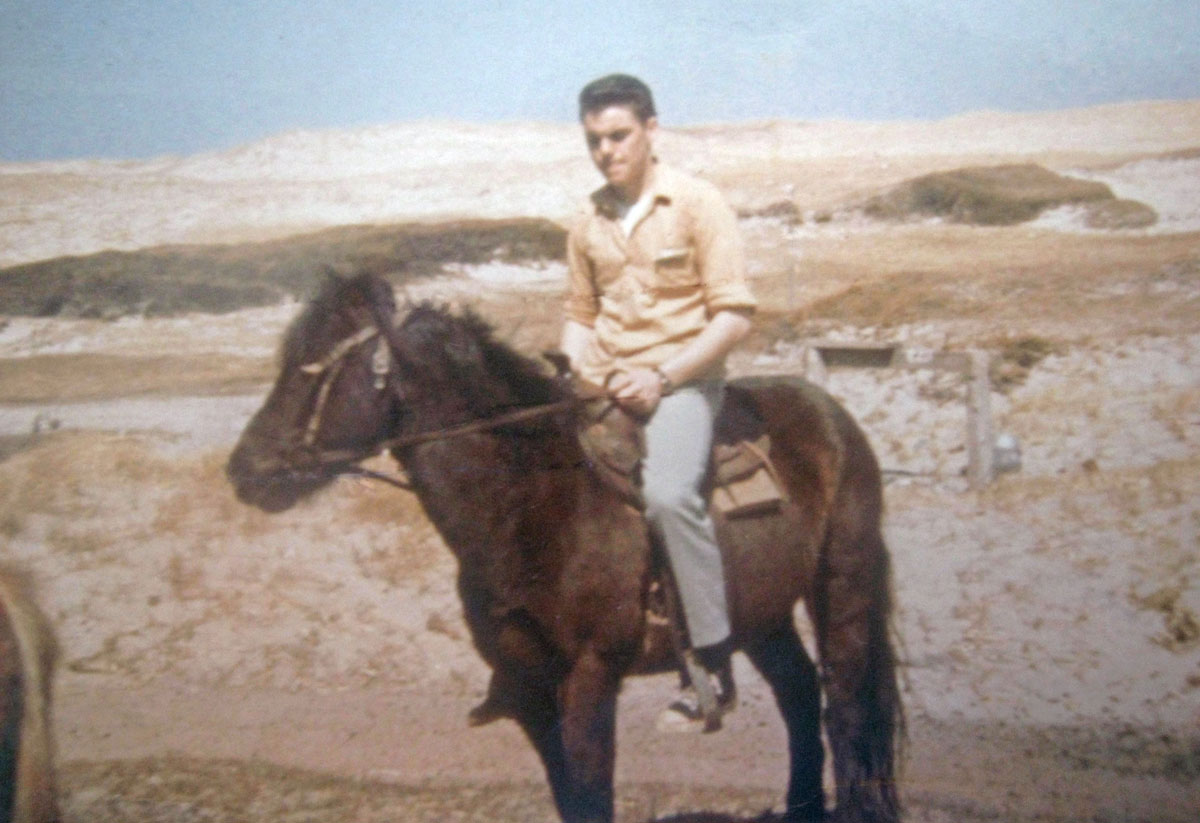

Gordon LeBlanc riding Sable Island horse Rawin, 1964 (photo provided by Gordon LeBlanc).

At the tender age of nineteen I joined the Meteorological Service of Canada, now a division of Environment and Climate Change Canada, as an upper air technician. This career saw me move around the eastern Canadian mainland, but I started off on Sable Island, the smallest landmass that I could have been sent to.

My one-year posting began on December 23, 1963. I was excited about starting a new career, and about the financial rewards that would come with isolation pay, potential overtime and a location where I would have a tough time spending the money that I made.

The work was largely routine, with a regular schedule of releasing the high atmosphere weather balloons and making detailed observations and measurements around the clock.

The station on Sable was staffed with six technicians and three full time staffers along with their spouses. This sounds like it would be close knit and chummy group in such a small place. The reality was that the station ran on a 24-hour schedule, which meant that breakfast was an almost solitary event. Dinner would generally see most of us gathered together, and supper would bring everyone to the table, but in varying states of tiredness and/or needing to go to bed early for the approaching morning shift. Days off gave some overlap with one co-worker, but most of our time off was spent alone.

It was hard to find time to explore much of the island on a work day, so on a day off we might pack a sandwich and go for a good, long walk, or in the spring and summer ride our dependable horses, Rawin and Trigger. Most of us spent our time off in our room listening to music on headphones or reading. As far as reading went, we relied largely on books that we had brought with us, as the selection of books on Sable was very old and very dated.

Music was a more complicated, and more communal thing. As new hires, we soon learned to put in an order for a tape recorder, and await its arrival from the mainland. Once equipped, we could entertain ourselves and not disturb our shift working colleagues. To stretch our dollars, and expand our horizons a bit, we’d share our music collections. We tended to be more of a jazz/Pete Fountain crowd, but the Beatles were becoming big then. We tried to keep as current as possible, but staples like Elvis and the Big Bands rounded out our musical collections.

In the summer there would be visitors coming and going, but the rest of the year it might be six weeks before a plane or a boat would bring something new or someone fresh to talk to.

There was a yearly autumn request from our colleagues on the mainland for two one-meter square boxes of cranberries, which would be divvied up amongst them. I was on the receiving end of this after I left Sable. This task was eagerly taken up as it gave us something else to do. As I gathered the cranberries, I reflected on the fact that the horses did not seem interested in the tart, but plentiful berries.

Of more direct benefit to us was a different type of gathering that took place over the course of a month. In those days, fishing nets were held up by hollow aluminum balls. These balls would inevitably dislodge and subsequently wash up on the shores of Sable Island. We’d set out on ponies to collect the balls, which we affixed to long ropes for transport. If we weren’t careful, the balls would clatter together on the ride back, startling the ponies and giving us more excitement than we needed. Not only did this task give us a diversion, but we would turn the aluminum in for money to be used to configure a television antenna. Our T.V. reception relied on temperature inversions placing the clouds just so to capture the mainland signals. Commercial radio signals were not much more reliable.

As much as the days could be routine or even lonesome, there was the occasional remarkable event to punctuate my year.

Easter arrived in March, and it found me with the day off. To pass the time, I rode Rawin to the East Light Station. This was a two-hour journey on a hard beach at a walk and trot. Once at East Light I climbed the tower, vainly hoping to get a glimpse of Nova Scotia. I did however, spot a ship offshore and the ship’s crew spotted me. Curious or concerned about the sight of a lone figure at the top of the tower, the captain soon dispatched a helicopter to investigate.

The ship was the CSS Hudson, a Canadian Oceanographic Service research vessel in its maiden year. Finding me well, the crew hospitably invited me to Easter dinner on the ship. After a good meal, and fresh conversation, I was returned to Sable by helicopter with enough time to make the journey back to join my colleagues for supper. When I told them I was not hungry because I had my Easter meal on the Hudson, no one believed me.

We were also visited by Melville Bell Grosvenor of the National Geographic Society for a feature about Sable Island. Grosvenor, Alexander Graham Bell’s grandson, stayed for several days, but a staff photographer soon followed. With many lenses and a box of film, he stayed for several weeks to get a more thorough account of the island. Nobody would doubt me on this story, as an image of me riding one of the ponies on the beach was immortalized in the pages of that venerable magazine.

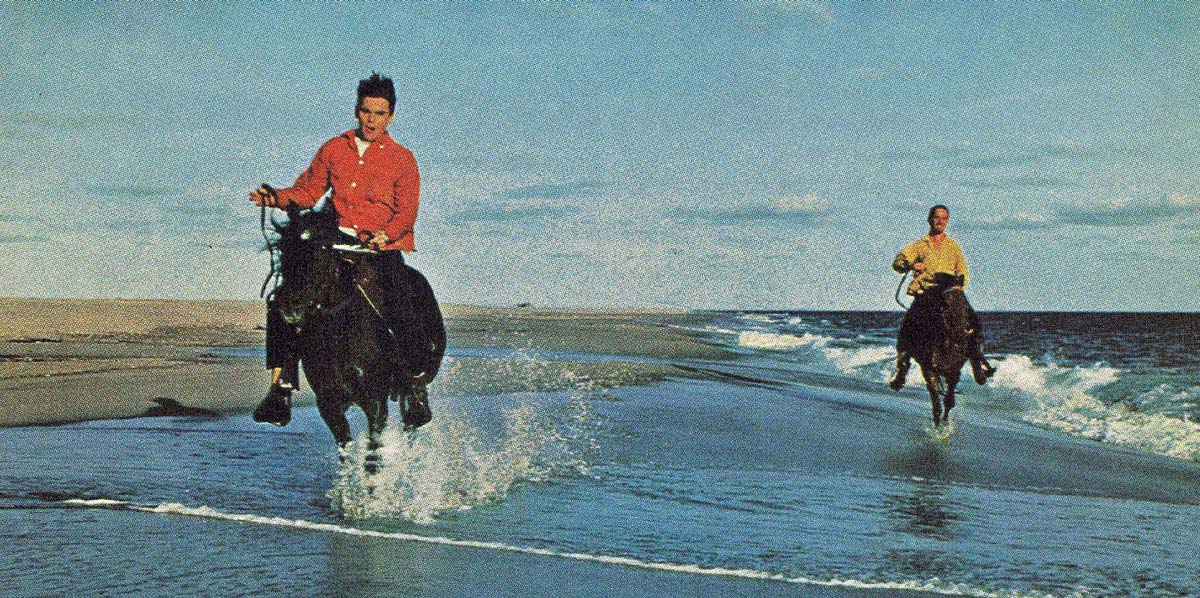

MSC meteorological technicians Gordon LeBlanc and Harry Earle riding on the south beach, 1964 (National Geographic, 1965).

MSC meteorological technicians Gordon LeBlanc and Harry Earle riding on the south beach, 1964 (National Geographic, 1965).

Financially, my time on Sable Island treated me pretty well. While I did not get rich by any means, in my year I saved as much money as I had earned the prior year working at a shoe store.

My career progressed nicely as well. I gradually worked my way up to upper air inspector. Following moves which took me from Labrador to suburban Toronto, I returned to the Maritimes to stay. As superintendent of station operations for the Atlantic region, with oversight of Sable, I managed the comings and goings to the island and kept in touch with its residents. In my tenure the T.V. and radio reception was vastly improved. I even had the pleasure of personally delivering “Pong”, the vanguard of the coming gaming revolution, to the staff on the island. I retired in 1995 while holding this office; with Sable Island neatly bookending my meteorological career.

As told to Susan Stark by Gordon LeBlanc

prepared by Susan and Geoff Stark for the Sable Island Institute, November 2019

Notes (ZL):

1. The horse’s name “Rawin” is a meteorological term for a radiosonde wind observation.

2. The CSS Hudson, an offshore oceanographic and hydrographic survey vessel, named for the explorer Henry Hudson, entered service in February 1964 with the Canadian Oceanographic Service. Among its scientific voyages is the first circumnavigation of the Americas, made in 1970. The ship was transferred to the Canadian Coast Guard in 1996 and remains in service as the CCGS Hudson, based at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

3. The National Geographic article referred to is “Safe landing on Sable Island – Isle of 500 Shipwrecks”, by Melville Bell Grosvenor, pages 398-431, in the September 1965 issue, Vol 128, No 3.

For more information about the Met Service on Sable Island, see:

MSC’s Aerological Program Ends After 75 Years of Service

Merlin MacAulay (1955-1956)

David Millar (1967-1969)

One Response

So, after reading about Sable Island in National Geographic, and finding out I was being posted to the weather station there… I bought overalls and a straw had for what I was expecting to be part of my attire for ‘Mucking’ out the horse stalls while on duty. Little did I know, the barn duties had been ended 5 years before I arrived for my one year assignment.