Image above: Dunes along north beach. The slopes down to the beach appear to be sparsely vegetated, but these are areas where marram grass has been affected by the feeding activities of cutworm. The Sable Island Cutworm Moth (wingspan ~3.5 to 4.0 cm) is a species found only on Sable Island. The larvae of this sandy-looking moth (rough sketch based on specimens) may be one of several species feeding on the grass.

During spring and early summer on Sable Island, conspicuous patches of dead and dying grass are common on dune slopes along the beach and in inland fields. They’re not the result of drought, grazing, cinch bugs, or other causes familiar to backyard gardeners, but instead are areas where caterpillars are feeding on American Beach Grass or American Marram Grass (Ammophila breviligulata).

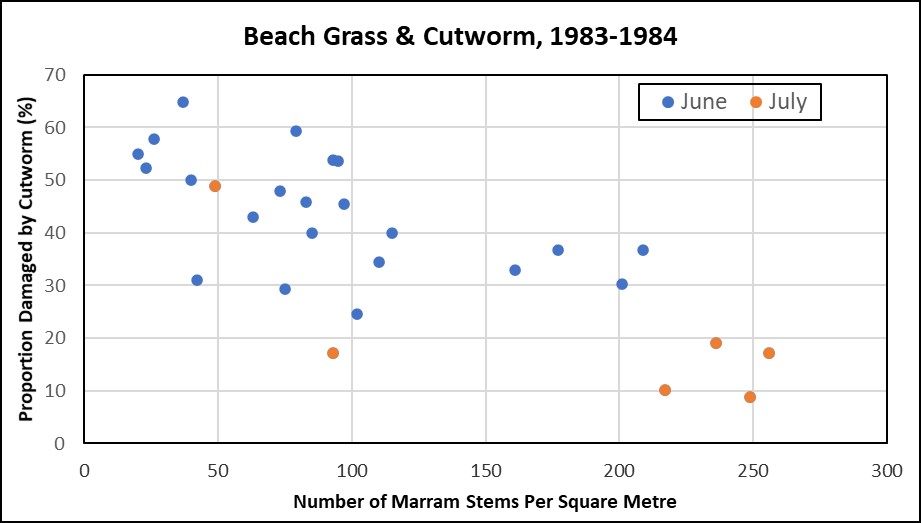

Patches of dead marram were noted in the early 1980s and some preliminary sampling provided numbers for damaged stems and the occurrence of caterpillars in stands of marram (Earlier Observations, 1983-1984). More recently, casual observations indicate that the distribution and extent of caterpillar activity have increased, especially since 2015.

Noctuid Moth Larvae

“Caterpillar” is a common name for the larval stages of moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera). The damage on Sable Island may be caused by the larvae of noctuid moths, commonly known as owlet moths, cutworms, or armyworms. The Noctuidae are a very large family of moths, with >3,000 species in North America, and some are considered to be serious agricultural pests. The larvae of most noctuid moths feed on plants, and while some species can be highly destructive to commercial field crops, gardens, and fruit trees, most have an important role in balanced and healthy natural environments.

Some species feed on foliage, others chew through plant stems at the base. They get their name from the behaviour of “cutting” off a plant at or just below ground level by chewing into or through the stem. In most cases, the entire plant is destroyed — the stems and leaves wither and die.

Although the term “cutworm” applies to the larvae of noctuids, not all noctuid species are cutworms, and some moths whose larvae have very similar feeding behaviours are not noctuids. Cutworms are often confused with the grubs of beetles that also damage plants (e.g., June Beetles, Phyllophaga drakii, which are common on Sable Island).

Life Cycle and Feeding Behaviour

Noctuids have the same general life cycle as other moths, consisting of four stages: egg; larva (caterpillar), which molts several times as it feeds and grows; pupa, which is a non-feeding, quiescent stage; and winged adult. Some species have only one brood a year, while others may have as many as five or six. Different species overwinter at different stages in their life cycle: some as pupae, either underground or in above ground cocoons; others as caterpillars; and some as eggs or adults.

Because of its foraging activity and the damage caused to vegetation, the larva is usually the most conspicuous stage in the moth’s life cycle. Unlike the adult moth, the larva has strong mandibles and other mouth parts for cutting and chewing plant material.

The preferred food plant of noctuid larvae varies depending on the species. Some species feed on a few specific plants, while others may eat a wide variety. The adults of species with preferred food plants lay their eggs near or on those host plants, thus providing the larvae with the preferred food as soon as the eggs hatch.

Cutworm larvae vary in their feeding behaviour; some remain with the plant they cut down and feed on it, while others move on after eating a small amount. The latter behaviour greatly increases the impact on vegetation (and appears to be the feeding habit of cutworm that are eating Sable Island’s marram grass). Most cutworms feed at night. Nocturnal activity and spending less time feeding on each plant may be strategies for avoiding predators, such as predacious insects and parasites (tachinid flies, parasitic wasps, ground beetles), and birds.

Adult moths do not damage plants. The adults usually feed on nectar from flowers or other liquid food sources such as tree sap. Like other butterflies and moths, members of the Noctuidae family have an important role in plant pollination.

Noctuid moth species identified as serious agricultural pests tend to be well studied. However, for many species which are not responsible for significant damage to crops and gardens, food storage, fabrics, and other products, little is known about their biology and ecological relationships. For some, only the adult stage has been identified and described, with no information available about the larval stages, food plants, and feeding behaviour. Although they feed on marram grass, the activities of the larvae may contribute in other ways to the health of marram communities.

A Photographic Review of Noctuid Moth Larvae Impact on Marram Grass, Sable Island

A stand of American Beach Grass or American Marram Grass (Ammophila breviligulata). The yellowed stems and leaves and their distribution in the stand are indicators of cutworm activity. The larvae or caterpillars have eaten into, or through, the stems just below the sand surface.

A stand of American Beach Grass or American Marram Grass (Ammophila breviligulata). The yellowed stems and leaves and their distribution in the stand are indicators of cutworm activity. The larvae or caterpillars have eaten into, or through, the stems just below the sand surface.

Cutworm damage in a denser patch of marram grass. Here also, the caterpillars have chewed the stems—usually at a single place on each—just below the sand surface.

Cutworm damage in a denser patch of marram grass. Here also, the caterpillars have chewed the stems—usually at a single place on each—just below the sand surface.

Areas of more recent cutworm activity can be recognized by the discoloured stems and leaves, yellowing but still having a trace of green.

Areas of more recent cutworm activity can be recognized by the discoloured stems and leaves, yellowing but still having a trace of green.

After the cutworm has fed on the below-ground part of a stem, the stem is generally held in place by a small section or shred of intact plant tissue and supported by the surrounding sand. The damaged stem will easily come away with a very gentle tug, and its end shows obvious signs of having been chewed.

After the cutworm has fed on the below-ground part of a stem, the stem is generally held in place by a small section or shred of intact plant tissue and supported by the surrounding sand. The damaged stem will easily come away with a very gentle tug, and its end shows obvious signs of having been chewed.

Generally, most have been damaged by a single cut where cutworm has fed at one spot on the stem just below the sand surface.

Generally, most have been damaged by a single cut where cutworm has fed at one spot on the stem just below the sand surface.

When scouting marram areas for cutworm activity, the number and distribution of discoloured, dead and dying stems and leaves are easily recognized indicators. With a very light pull, stem damage can be confirmed. This is helpful because amongst the discoloured stems and leaves, there are plants so recently chewed that they are still entirely green and healthy-looking.

Marram Grass Communities Affected by Cutworm

Inland Areas

What appears to be a stretch of sparsely vegetated terrain on an inland dune is actually an area where marram grass has been heavily damaged by the feeding activity of cutworms. The discernible line or edge between affected and unaffected plants is commonly seen in cutworm sites on the island.

What appears to be a stretch of sparsely vegetated terrain on an inland dune is actually an area where marram grass has been heavily damaged by the feeding activity of cutworms. The discernible line or edge between affected and unaffected plants is commonly seen in cutworm sites on the island.

A closer view of the site in the previous photo, showing most of the marram damaged by cutworm, with some live plants scattered amongst the dead.

A closer view of the site in the previous photo, showing most of the marram damaged by cutworm, with some live plants scattered amongst the dead.

A patch of cutworm activity on a high inland dune west of Gallinule Pond. The darker, denser green vegetation at the far side of the patch is mostly bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica).

A patch of cutworm activity on a high inland dune west of Gallinule Pond. The darker, denser green vegetation at the far side of the patch is mostly bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica).

A small, isolated patch of cutworm activity in a vigorous stand of marram grass on a gentle south-facing slope with some recent sand accumulation. A few Seaside Goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens) plants near the edge of the patch show no damage. Sand accumulation may have held the dead stems and leaves in place.

A small, isolated patch of cutworm activity in a vigorous stand of marram grass on a gentle south-facing slope with some recent sand accumulation. A few Seaside Goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens) plants near the edge of the patch show no damage. Sand accumulation may have held the dead stems and leaves in place.

In another inland site where there has been little sand accumulation and more wind scouring, most of the dead marram has blown out, leaving some clumpy growth of surviving marram amongst the ragged and flattened remains of dead plants.

In another inland site where there has been little sand accumulation and more wind scouring, most of the dead marram has blown out, leaving some clumpy growth of surviving marram amongst the ragged and flattened remains of dead plants.

South Beach Dunes

Dunes along the inside (northern edge) of the Sandy Plain area of south beach (a view from the beach, looking to the north). Feeding by cutworm has left a well-defined boundary between dead plant material and stands of live, unaffected grass.

Dunes along the inside (northern edge) of the Sandy Plain area of south beach (a view from the beach, looking to the north). Feeding by cutworm has left a well-defined boundary between dead plant material and stands of live, unaffected grass.

Close-up of damaged marram shown in the previous photo. In this cluster of plants, most of the green stems and leaves were intact, they had not been cut.

Close-up of damaged marram shown in the previous photo. In this cluster of plants, most of the green stems and leaves were intact, they had not been cut.

Another view of dunes along the inside of the Sandy Plain area of south beach (a view from the beach, looking to the northeast) showing a broad area of grass damaged by cutworm.

Another view of dunes along the inside of the Sandy Plain area of south beach (a view from the beach, looking to the northeast) showing a broad area of grass damaged by cutworm.

During 2016, cutworm feeding activity appeared to be heavier on the south side, particularly in marram communities on low dunes along the edge of the Sandy Plain. In these areas, the dead plant materials were supported by surrounding sand and held in place long enough to be partially buried by wind-blown sand rather than being scoured away. This buried plant ‘litter’ contributes some organic matter to the sandy soil.

Sandy Plain Hummocks

One of the numerous embryo dunes (known as the “Hummocks”) on the Sandy Plain. Throughout the area, most of the cutworm activity was evident on the south and southeasterly sides of these small, isolated dunes.

One of the numerous embryo dunes (known as the “Hummocks”) on the Sandy Plain. Throughout the area, most of the cutworm activity was evident on the south and southeasterly sides of these small, isolated dunes.

North Beach Dunes

During 2019 and 2020, cutworm activity was especially heavy along the north side of the island.

During 2019 and 2020, cutworm activity was especially heavy along the north side of the island. A close-up of the upper slope of the dune face in the previous photo, showing the characteristic edge or boundary between damaged and undamaged marram.

A close-up of the upper slope of the dune face in the previous photo, showing the characteristic edge or boundary between damaged and undamaged marram.

Extensive cutworm damage on the beach facing slopes of dunes along the north side.

Extensive cutworm damage on the beach facing slopes of dunes along the north side.

A close-up of the upper slope of the dune face in the previous photo. Unlike the cutworm areas on the south beach in 2016, here the damaged marram has been scoured out by wind, with further erosion of sand.

A close-up of the upper slope of the dune face in the previous photo. Unlike the cutworm areas on the south beach in 2016, here the damaged marram has been scoured out by wind, with further erosion of sand.

An area similar to that shown in the previous photo, but this location has had a small amount of sand accumulation since the earlier scouring of dead plant material and sand.

An area similar to that shown in the previous photo, but this location has had a small amount of sand accumulation since the earlier scouring of dead plant material and sand.

North Side of West Spit

Three mid-June views of a long, narrow strip of cutworm activity, running parallel to the beach, along the north side of the West Spit. Here the remains of damaged marram have been partly blown out and flattened, and partly buried by wind-blown sand.

Three mid-June views of a long, narrow strip of cutworm activity, running parallel to the beach, along the north side of the West Spit. Here the remains of damaged marram have been partly blown out and flattened, and partly buried by wind-blown sand.

In these sites, the timing, direction, and amount of sand movement—erosion and accumulation—influences the recovery of the marram grass. Where recovery is weak, the affected areas are vulnerable to further scouring by wind.

Other Plant Species

Beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus) is unaffected by the cutworm activity that has killed most of the surrounding marram. So far, similar cutworm damage has not been observed in other plant species on the island.

Beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus) is unaffected by the cutworm activity that has killed most of the surrounding marram. So far, similar cutworm damage has not been observed in other plant species on the island.

Late Summer Recovery

During late July and August there’s some recovery in many areas affected by cutworm. New growth involves both plants that had not been damaged, and propagation from underground stems and rhizomes.

During late July and August there’s some recovery in many areas affected by cutworm. New growth involves both plants that had not been damaged, and propagation from underground stems and rhizomes.

With most of the original above-ground parts of the plant dead, new leaves and stems develop from underground material.

With most of the original above-ground parts of the plant dead, new leaves and stems develop from underground material.

In areas where there is some sand accumulation, the regrowth has a healthier look.

In areas where there is some sand accumulation, the regrowth has a healthier look.

Three locations along north beach, between the Sable Island Station and East Light. Although there is new growth of marram in each, the area of past cutworm activity is still obvious. Some who are less familiar with the island’s dune vegetation communities and the foraging behaviour of the Sable Island horses, have mistakenly attributed the conditions in cutworm-affected areas to the grazing activity of horses.

Three locations along north beach, between the Sable Island Station and East Light. Although there is new growth of marram in each, the area of past cutworm activity is still obvious. Some who are less familiar with the island’s dune vegetation communities and the foraging behaviour of the Sable Island horses, have mistakenly attributed the conditions in cutworm-affected areas to the grazing activity of horses.

Noctuid Moths on Sable Island

As earlier noted, given the pattern of damage observed (see photos above), and known feeding behaviours of noctuid larvae, cutworms are most likely responsible for the patches of dead and dying marram seen on the island.

Over 40 species of noctuid moths have been recorded on Sable Island so far. Most of the early work to survey and list the island’s moths and butterflies, including the description of new species, was conducted by Barry Wright (Nova Scotia Museum) (Wright 1989), and by Kenneth Neil (Dalhousie University, and Agriculture Canada, Research Station, Kentville, NS) (Neil 1977, 1979, 1983 & 1991).

Among the noctuid species that may be feeding on the island’s marram grass are the Sandhill Cutworm (Euxoa detersa), and the Sable Island Cutworm (Agrotis arenarius). During collection work in the 1970s and early 1980s, the adults of both species were more often recorded at locations where marram grass was abundant.

Euxoa detersa, Sandhill Cutworm.

Although found from Newfoundland south to North Carolina, west to Nebraska, and north to Alberta and the Northwest Territories, this species was originally described from Nova Scotia (Wright 1989). In 1989, Barry Wright wrote that this cutworm “is not well represented in collections from the mainland where it is confined to coastal localities in the southern part of the province, but it is abundant on Sable Island where the population is comparatively pale and grey.” Wright (1989) noted that in July the larvae moved over the sand surface at night, and adults were recorded at lights from mid August to the end of September.

In general, this species occurs in sandy habitats, including beaches, dunes, and fields with a high percentage of sand in the soil. The larvae are known to feed on corn, grasses, cranberry, sea-rocket, various garden crops and commercial grains. They cut plants below the soil surface and can cause much destruction in crops planted in sandy soils. This cutworm has one generation per year. It hatches in the fall, then overwinters as a partially-grown larvae. Feeding resumes in the spring and continues until mid-summer (May through to mid-June). Adults emerge in July-August and lay their eggs.

Agrotis arenarius, Sable Island Cutworm.

This moth species is an endemic, found only on Sable Island. It was first identified by Kenneth Neil (Neil 1983). Larval stages are as yet undescribed and little is known about its biology and behaviour. Wright (1989) noted that its “colour and maculation is cryptic for resting on dead grass”, and this, along with it having been being found most often in marram-dominated communities, suggested the larva is a “subterranean feeder on roots and shoots” of marram.

Although these two species may be involved in the damage to the island’s marram grass, the larvae of other moth species, including some that are not noctuids, could be contributing to, or primarily responsible for, the patches of dead and dying marram on Sable Island.

As research on the island’s insect communities continues, there may be additions to the list of moths found on the island. So far, five endemic species, species that occur only on Sable Island, have been recorded. These are the above-mentioned Sable Island Cutworm, and four others: Sable Island Bordered Apamea (Apamea sordens sableana), Sable Island Eucosma (Eucosma sableana), Sable Island Borer (Papaipema sp.), and White-marked Tussock Moth (Orgyia leucostigma sablensis). All five are high priority candidates for assessment by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Like the Sable Island Cutworm moth, the Apemea is a noctuid.

Little is known of the feeding habits of Sable Island Bordered Apamea. However, it is a subspecies of Apamea sordens (common name Rustic Shoulder-knot or Bordered Apamea), a moth that is widely distributed in North America (Labrador to Virginia, west across Canada, and south to Minnesota). Its larvae, known to cause serious economic damage to grain crops such as wheat, rye, and corn, is a “climbing cutworm”, named for its habit climbing plants to feed on foliage. This feeding behaviour is not consistent with the damage to marram grass observed so far on Sable Island.

Earlier Observations, 1983-1984

In the early 1980s, during the dune restoration program, cutworm activity was noted in some areas where marram plants were being collected for transplanting into restoration sites. Also, some localized damage among transplants in the A9 site was attributed to feeding by cutworm during early summer of 1982. Although there appeared to be less cutworm activity in 1983, the affected plants showed only limited recovery (Lucas 1988). To assess the impact on marram, a preliminary study was undertaken during mid-summer in 1983 and 1984.

Twenty-eight plots were established in marram-dominated communities in four locations on the island. Most (21) were in a broad inland field of marram then known as the Green Plain. Sample periods were June 28-30 (13 plots) and July 6-13 (6 plots) in 1983; and June 14-22, 1984 (9 plots).

Plot quadrats of 1 m2 were established randomly, roughly 10 to 20 m apart. In each plot, the total number of green, and still partially green, stems, and the number of those damaged by cutworm, were recorded.

Following the counts, each plot was excavated to a depth of about 30 cm (with marram plants carefully removed so that they could be replanted), and the sand was sifted for cutworm larvae. Other larvae, such as June Beetle, were recorded.

When completed, marram, larvae, and excavated sand (which had been piled on a tarp) were replaced. When checked several weeks later, the plots showed little loss of live plant cover, aside from cutworm damage.

Results

All 28 plots showed recent cutworm activity. Feeding damage on the marram stems was ~2-5 cm below the sand surface, but this value could be affected by sand movement during the period between cutworm activity and sampling.

A total of 3,106 stems were counted, of which 981 (31.6%) had been damaged by cutworm. The number of stems/plot ranged from 20 to 256 (x̅ 110.9, SD 72.7, n=28), and the amount of cutworm damage/plot ranged from 8.8% to 64.9% (see figure below). The rate of damage was greater in plots with fewer plants. The highest cutworm damage was recorded in the 15 June-sampled plots having <100 stems/plot (x̅ 62.1, SD 27.9, n=15). Eight plots had damage rates ≥50%, and all these were plots having <100 stems.

The rates of cutworm damage observed in June 1983 and June 1984 were similar, 40.5% and 39.5% respectively.

Moth larvae (at least two species, but not identified) were found in 27 of the 28 plots, ranging from 0 to 13 larvae/plot, with an average of 6.5 larvae/plot. In the single plot where no larvae were recorded, recent cutworm activity was observed. Also, June Beetle larvae were found in 15 of the 28 plots.

Although this preliminary survey provided only a few slim insights, it raised numerous ecological questions. However, the work was not continued partly because cutworm damage in stands of transplanted marram was minimal, being absent in most of the restoration sites, but mostly because the program lacked sufficient resources.

Sable Island Institute Noctuid Moth Program

All this information suggests that the noctuid moths and their larvae have an ecological role on the island far bigger than their tiny size suggests. Understanding the intricacies of Sable Island’s hidden relationships is exactly what the Sable Island Institute’s approach to science is all about, and what could typify that more than this tiny worm-like creature hidden just under the sand’s surface?

So it’s no surprise that Institute is making cutworms the focus of its first major terrestrial research program on the island. Our fieldwork starts in spring 2021, so we’re now hard at work on literature reviews, consultations, and proposals to Park Canada and funding sources.

Our specific goal is to understand which factors influence the cutworms’ distribution and impact on the island across all scales: both ecological scales, from the foraging paths of individual caterpillars to the impact of cutworm activity on the birth and death of dunes, and temporal scales, from the life cycle of these insects within a season to their population trends across years. To do that, we need to answer key questions that start from basics (like which cutworms are involved and what their lifestyles are) and build up to bigger issues (like how and where cutworms have the most impact, and where are they steering the island’s ecology over the long term). Here’s a brief sketch of this research program:

What noctuid moth species are involved?

The Sandhill and Sable Island Cutworms are just two of the many invertebrate species that might be affecting marram across the island. So a first step in our research is to identify the cutworms and other insects that are affecting the vegetation. We’ll be using light traps to identify adults, but many caterpillars are so hard to identify that one needs to raise them to adulthood to know which species they are. Once that’s done, we can create a photographic key to the island’s caterpillars that will allow quick field identification of the main species.

What’s the life cycle of the noctuid moths?

Our collecting and identifying will help answer a host of basic questions about the cutworms, like when and where eggs are laid, how many generations are produced per year, and where and at what stage cutworms overwinter. Meanwhile, we’ll also conduct field surveys by day and night, to determine when and where larvae and adults rest or are active, what plants they feed on, and how they plan their foraging routes through the environment – all patterns that will be further tested with lab studies. The field surveys will also help us identify likely predators of the cutworms – again subject to testing, both in the lab and in the field.

What are impacts?

Agricultural studies show that some crops, such as flax and peas, can compensate for cutworm damage, while others, such as corn, tend not to. That kind of variation is likely across plant species on Sable, too, and also across different growth patterns of marram. Thus we’ll survey cutworm effects across the island, not only direct effects on vegetation, but also knock-on effects on sand transport and retention. All these effects will likely interact with other factors, notably grazing by horses and dune morphology, so this is where the integrative, collaborative nature of the research program will be most apparent.

What are noctuid moth and larvae trends across the island and through the years?

The research on impacts just outlined will inevitably involve mapping of cutworm impacts on to vegetation and landscape features. This identification of features that predict high or low cutworm effects will give us tools that can expand the mapping across the island and across years, even well before our study begins. Georeferenced vegetation and landscape data for Sable Island stretches back decades, so we’ll be able to determine whether affected or at least vulnerable areas have increased, and those trends correlate with variation in weather or broad changes in the island’s climate.

References

Lucas, Z. 1988. Terrain restoration activities, pages 7-32 in Terrain Management Activities on Sable Island 1982-1985, ed. R. B. Taylor, Terrain Subcommittee, Sable Island Environmental Advisory Committee.

Neil, Kenneth. 1977. An annotated list of the macrolepidoptera of Sable Island. Proceedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science, Vol 28, Part 1/2: 41-46.

Neil, Kenneth. 1979. A new species of Orgyia leucostigma (Lymantriidae) from Sable Island, Nova Scotia. J Lepidopterists’ Society, 33(4): 245-247. [entomology, lepidoptera]

Neil, Kenneth. 1983. A new species of Agrotis Ochs. (Noctuidae) from Sable Island, Nova Scotia. J Lepidopterists’ Society, 37(1); 14-17.

Neil, Kenneth. 1991. The larva of Ommatostola lintneri (Noctuidae: Amphipyrinae). J Lepidopterists’ Society, 45(3): 204-208.

Wright, Barry. 1989. The Fauna of Sable Island. Curatorial Report Number 68, Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, NS, pages 1-93.

Zoe Lucas and Andy Horn

Sable Island Institute, July 2020

One Response

Fascinating and important. Please keep us posted.